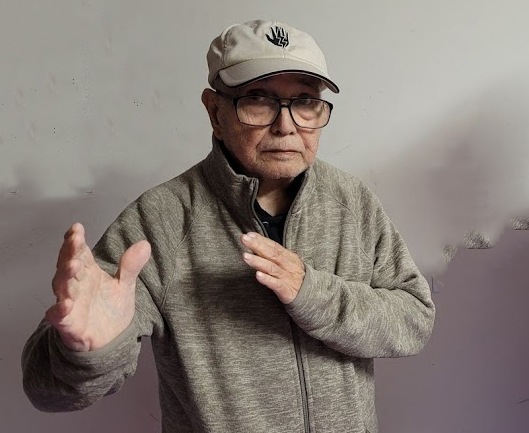

I was recently afforded an opportunity to talk to a collected group of specialists about my experiences adapting classical martial principles, training, and even technique to modern policing applications. The audience included a few others who have a foot in both classical training and modern policing, and I am very thankful to Ellis Amdur, my koryu instructor, and to Mr. Liam Keeley for that opportunity.

Ellis’ teacher demanded that budo be applicable not simply in everyday life, but in “moving the world” in ways of consequence, and Ellis feels the same. As do I. Picture the tiger in the wild, not in a cage, and certainly not stuffed and displayed as a museum piece. This approach may be regarded as somewhat outside the norm in the larger koryu community. Some might ask how archaic martial arts, with whatever small bits any particular tradition may preserve of an actual combative curricula, could apply in any practical sense in today’s world, particularly when many practitioners themselves don’t see things that way.

One word: Uvalde.