Part 3 – Later Historical Record of Yagyū Shinkage-ryū

There is little written about Yagyū Shinkage-ryū as it was in the 1700s. Renya’s nephew Toshinobu succeeded him as head of the family and instructor to the Owari Tokugawa. He took the ryū into the 18th century, and then passed it on to his son Toshitomo, who then passed it on to his son Toshiharu.

Nagaoka Fusashige

One of Toshiharu’s students was a man named Nagaoka Tōrei Fusashige. Nagaoka inherited from his father the position of shihan-hosa, assistant instructor to the sōke. Nagaoka’s official post in the Owari Domain was to train martial arts, particularly Shinkage-ryū, and to write about them. Toshiharu was succeeded by his son Toshiyuki, but Toshiyuki died at a relatively young age, and was succeeded by his teenage son, Toshihisa. But then Toshihisa also died at age 20, when his own son, Toshishige, was still a baby. Toshiharu’s younger brother, Toshimasa, together with Nagaoka, kept things together until Toshishige could come of age and grow into his role as sōke.

One thing Nagaoka noticed was that people were struggling in shiai. His solution was to devise more kata. He referred to these kata as seihō (勢法) to distinguish them from the original kata of the ryu, which are called tachi 太刀. The sei refers to ikioi, which means force and momentum, but also carries a nuance of the natural course of things. Hō refers to methods and principles. In the preface to his description of these seihō, Nagaoka wrote:

There are many beginners who do not understand the way to achieve victory in shiai, and then go headlong down the wrong road. So I, Fusashige, have devised seihō in the broad outlines of shiai, with the teachings of the past masters, based on the forms of certain victory in the old [armored] style and new [unarmored] style, and give them to my fellows in order to begin their study. [1]

What are the shiai-seihō and what makes them different from the tachi so that they can aid the learner in shiai? Most of the tachi (Empi no Tachi being the notable exception) are split into distinct parts which are made up of one or two exchanges between the practitioners. The shiai-seihō typically feature three or four exchanges chained together, some even have eight or nine, and some of them have effectively no upper limit, bound only by physical space and uchidachi’s wherewithal. They are also dynamic: within these multiple exchanges, attacks and responses come from high and low, from left and right and from far out and close in, with both shidachi and uchidachi moving forward or back. After the new practitioner has learned the first three shiai-seihō, totaling thirty distinct sections, they have acquired the basic skill to respond to an attack from any angle, to any target on their body. Finally, they are highly permutable. Different seihō share similar parameters, so that one can flow into another, or the response in one might be used in a different, but similar seihō.

Nagaoka’s description of Gasshi, the very first part of the first shiai-seihō, is also very interesting from the perspective of historic shiai. (Here is a description in case the link above should ever break; shidachi and uchidachi start standing roughly thirty feet apart, and with shinai held overhead, both approach the middle. They stop at a point with both just a little outside striking distance. Uchidachi takes a big step forward with their right foot, cutting straight. In response shidachi does the same, a big step forward with their right foot, cutting straight. The slight delay in shidachi’s response allows them cut over uchidachi’s cut, deflecting it to the side as shidachi’s shinai lands on uchidachi’s head. Both then step back, and do it again, this time cutting with the left foot.)

Nagaoka writes: “In the past, this was a type of higiri-jiai. Now we use the winning form of this shiai as a seihō.”[2]

I will talk about the meaning of higiri in the next part of this series, but there are three clear takeaways from these statements by Nagaoka. One is that shiai was a part of regular practice, and indeed that even beginners engaged in it. Two, we see issues with shiai being addressed with more kata. Third, with the statement “Gasshi is a type of shiai,” we can see that there are multiple parameters for shiai. It can be as open as a modern kendo shiai, or as limited as both practitioners in jōdan, both cutting straight against each other.

Yagyū Toshichika

Moving on, young Toshishige eventually grew up and inherited the ryū and the hereditary position as heihō instructor. His son was Yagyū Sangorō Toshichika, the 19th sōke of Shinkage-ryū, and the last heihō instructor to the Owari Tokugawa. He oversaw the transition of the ryū from the Bakumatsu to the Meiji Era.

In 1868, Lord Yoshikatsu, the last lord of Owari and 18th sōke of Shinkage-ryū, opened the Meirindō, one of the early public schools of the Meiji era. As part of the school he also opened the Shidaibu Dōjō, and invited practitioners of various ryūha to do uchikomi-jiai. Toshichika was appointed the dean of kenjutsu instruction for the dojo. According to Yagyū Toshinaga in his book Shōden Shinkage-ryū, the Shidaibu Dojo was devoted purely to shiai. [3]

The dojo project deteriorated after various edicts, such as the Haitorei, which ended the era of the bushi as warriors, and made the various ryūha ostensibly obsolete. In later years, the Butokukai would be established to promote the training and transmission of classical and modern budō as a whole, but at that time Toshichika had decided to devote himself to purely passing down his family tradition of Shinkage-ryū.

I think what we have here is a major decision point for Shinkage-ryū. We can see the general trend towards shiai-centric practice, as well as an impetus towards involving multiple ryūha. Toshichika was intimately involved in that movement, at least as far as the Meirindō and Shidaibu Dojo were concerned. But either because of the experience, or in spite of it, Toshichika decided to step out of these movements, and focus on maintaining the essential character of Shinkage-ryū. We can imagine that had he chosen differently, Shinkage-ryū might have only survived in a few kata or pieces of kata in modern kendo.

On June 19th, 1885, Toshichika and his cousin Toshihiro traveled to Yagyū Village in Nara, and asked for a shiai with any of the former retainers of Yagyū Domain. I think it’s an interesting point that they did not offer to train or demonstrate kata, but that they wanted to see the vitality of the ryū in Yagyū Domain through a shiai. [4]

Yagyū Toshinaga

In 1913, Toshichika opened the Hekiyōkan Dōjō in Tokyo, and began teaching Shinkage-ryū to the Imperial Household Police. Toshichika’s son, Toshinaga, accompanied Toshichika to Tokyo, and was named sōke in 1922. He took over the Hekiyōkan after Toshichika retired back to Nagoya, and later opened the Kongōkan Dōjō, where he practiced until returning to Nagoya in 1935. While in Tokyo, he also taught kenjutsu to the Konoe Shidan (Imperial Guard).

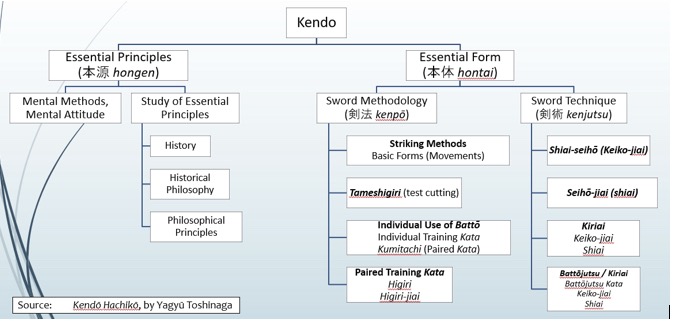

In 1935, Yagyū Toshinaga gave a weeklong lecture series at Kokushikan University. These lectures were collected into a book called Kendō Hachikō, (Eight Lectures on Kendō). Kendō here is meant is the broadest possible sense as including modern kendō and classical schools. And here we can see Toshinaga’s image of ideal training, informed by his experience in Yagyū Shinkage-ryū. [5]

- SWORD METHODOLOGY (剣法, kenpōi) is focused on the individual student, either on their own or as the shidachi of paired practice.

- SWORD TECHNIQUE (剣術, kenjutsu) operates in the realm of mutual practice (no distinct uchidachi/shidachi).

Toshinaga broke down his conception of training as follows:

- Kata here is written with the kanji for marudachi 丸太刀. The significance of this is that these represent the “classical” forms, the ones that act as containers for the founders’ insights. The exemplar of this would be Shinkage-ryū’s Sangaku En-no-Tachi 三学円之太刀. It is contrasted with seihō.

- Higiri (lit. “cutting openings”) is a level of paired practice wherein uchidachi bends or breaks the kata to strike shidachi when they leave an opening. Higiri-jiai is an advanced level where both uchidachi and shidachi do this. I will discuss this further in the final article in this series.

- Shiai-seihō references the Yagyū Shinkage-ryū sets of kata under the same name, but as I understand it, Toshinaga is here suggesting similar seihō created for general use, rather than the specific shiai-seihō of Yagyū Shinkage-ryū. Here Toshinaga shows how they can act as a bridge from the higiri-jiai of the kata to fully open shiai. Essentially, you would have two participants doing a shiai under the parameters of the shiai-seihō, both as part of intra-dojo practice, and then in a inter-dojo environment.

- Kiriai, then, is how he classifies fully open shiai between two competing individuals, in both an intra- and inter-dojo setting.

- Finally, you would have the same kind of progression with battō, though I must confess that I am less certain of how that would work. I’m not sure if we’re talking shiai versions of the kumitachi, side-by-side competitions like you see today, or perhaps even actual free draw-and-strike against an opponent type situation.

This series of lectures show that even into the 20th century, shiai was considered an important aspect of Yagyū Shinkage-ryū. Toshinaga would go on to shepherd Shinkage-ryū through the war and post-war years, eventually founding the Yagyūkai in 1955, before dying in 1967.

Yagyū Nobuharu (Toshimichi)

Toshinaga’s son, Nobuharu brought Shinkage-ryū to the 21st century, and accepted the first non-Japanese into the ryū that we know of. I want to wrap the historical examination by looking at his experience training during his teen years, as described in the book Dai-Sempai ni Kiku:

- “After practicing seihō they would don bōgu and try to actually strike each other with those techniques. About twenty primary school-age children would come to the dojo every Sunday, and [Toshimichi] was responsible for guiding them through basic practice. “[Nobuharu says,] ‘There was a spirit of, Let’s get some bōgu on and go at it freely, for real. Now I no longer have the old dojo, and time is limited, so we first work on the most important things.’” [6]

The old Nagoya dojo, part of the Yagyū manor, burned down in the fire-bombing of Nagoya in March of 1945, and the land was later appropriated by the city of Nagoya as part of the rezoning and reconstruction efforts. It was at this point, after the war, roughly four hundred years after the founding of the ryū, that Yagyū Shinkage-ryū moved to a kata-exclusive model. Nevertheless, it maintains a path to shiai, both in the content of the shiai-seihō, and also in how all kata are practiced. I will explore this path in the final part.

References

[1] 新陰流兵法外伝 Shinkage-ryū Heihō Gaiden (Shinkage-ryū Heihō Supplemental Teachings), date unknown, by Nagaoka Fusashige, published in Shiryō Yagyū Shinkage-ryū, ed. Imamura Yoshio, revised edition 1995.

[2] 新陰流兵法外伝 Shinkage-ryū Heihō Gaiden, ibid.

[3] 正伝新陰流 Shoden Shinkage-ryū, (True Transmission Shinkage Ryu), 1957, by Yagyū Toshinaga.

[4] 正伝新陰流 Shoden Shinkage-ryu, ibid.

[5] 剣道八講 Kendō Hachikō (Eight Lectures of Kendō), 1998, by Yagyū Toshinaga, ed. Yagyūkai.

[6] 大先輩に聞く Dai-sempai ni Kiku (Listening to our Great Seniors), 2005, by Taya Masatoshi.

Purchase Ellis Amdur’s Books On Budō & De-escalation of Aggression Here

Note: If any of my readers here find themselves grateful for access to the information in the essays published on this site, you can express your thanks in a way that would be helpful to me in turn. It would be most welcome if you were to purchase one or more of my books, be it those on martial traditions, tactical communication or fiction. In addition, if you have ever purchased any of my books, please write a review – the option is there on Amazon as well as Kobo or iBook. To be sure, positive reviews are valuable in their own right, but beyond that, the number of reviews bumps the algorithm within the online retailer, so that the book in question appears to more customers.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.