Bōnote (‘staff and hand’) is a festival-centered activity focused around small groups in the old Mikawa and Ryūsenji districts of Aichi. Collectively they hold numerous presentations at many local shrines and events in the surrounding areas, and have even flown overseas to demonstrate. For over 300 years, participants of bōnote have gathered at shrines to practice, organize and perform techniques with weapons as an offering to the ‘spirits of the altar,’ as well as parading new horses, and making offerings to ensure blessings and good fortune.

Bōnote was originally made up of groups called ryū or ryūha whose primary function was to teach prearranged training drills called kata to their members. The area where one lived decided which ryū each person belonged to, and the length of time spent performing, determined the ‘rank’ each person had, and what position they held in the group’s organization.

Bōnote was originally made up of groups called ryū or ryūha whose primary function was to teach prearranged training drills called kata to their members. The area where one lived decided which ryū each person belonged to, and the length of time spent performing, determined the ‘rank’ each person had, and what position they held in the group’s organization.

The kata of bōnote could be summed up as positioning, striking, and evading within set patterns. Going further, what is taught within those patterns is the number and frequency of striking; deflections, blocks and evasions; hand, leg, and body positions: all of which is accompanied by kakegoi (‘spirit yelling’).

A typical bōnote arsenal consists of bō (wooden sticks), yari (spears), uchigatana (disposable ‘side swords’), nagagama (war hooks), kama (sickles), naginata (glaives), and a host of others. Sticks are the primary training tool and a legitimate all-purpose substitute for the other weapons; they are what beginners start training with because authentic weapons are expensive and not something one wants to damage in training. Of course, they are also much safer.

Although many call what they do a ‘ritualistic dance,’ there is no set rhythm to it, nor is there anything that would fit the definition of a classical dance within Japanese culture. Bōnote does not look like a dance found in any traditional theater art: it is not enacted like a dance, it is not connected to any theater or performance group, and perhaps most importantly, it is not taught like a dance.

Training and performances begin under the clap of hyoshigi, two wooden pieces of wood tied together with string. The sound they make is indicative of the ‘clapping’ of the weapons during the performance, which is considered to be the ‘voice’ of bōnote. New arrivals to the school train in line-drills using wooden weapons under the watchful eye of their seniors. They are taught using a rigid instruction pattern, set by number, to enable them to fully memorize the basics. After becoming proficient in line-drills, they move up to other weapons and techniques, that starts out much the same way as the basic techniques, but with a much faster assimilation rate as an understanding of essentials has already been absorbed.

The origins of bōnote are unclear, as it has no direct starting point, and there’s nothing clearly defined about its history. The name itself arose by taking the most common training weapon’s name (bō) and mixing it with the term te-awase (‘hands coming together’) to form a new term: bōnote (‘stick and hand’). This phrase eventually became commonplace, and was used throughout Mikawa region to describe the practice.

The origins of bōnote are unclear, as it has no direct starting point, and there’s nothing clearly defined about its history. The name itself arose by taking the most common training weapon’s name (bō) and mixing it with the term te-awase (‘hands coming together’) to form a new term: bōnote (‘stick and hand’). This phrase eventually became commonplace, and was used throughout Mikawa region to describe the practice.

What is known is that bōnote has been around for a long time, almost as long as bona fide written records of the area have existed. It is referenced in multiple sources both inside and outside the region, and coupling this with the turmoil Japan experienced over the centuries, as well as fanciful story-telling and religious fervor, you have a very mixed bag of origin tales. The varied legends and oral history coming from the schools of bōnote state that it started somewhere in the Heian, Muromachi, or the Sengoku era (a range of over 800 years) focusing around two main origin themes: either bōnote (1) started in the Mikawa area as a type of farmer’s self-defense and militia or (2) started when Owari area shugenja (yamabushi – devotees of the Shugendō religious sect) began teaching the farmers techniques as a kind of ‘ward against evil spirits.’

It is connected heavily both with Sanage Shrine at the foot of Mt Sanage in Koromo city, Mikawa (now Toyota City, Aichi prefecture), and the area around the Ryūsenji temple and castle district (now in the Moriyama ward in Nagoya city, Aichi prefecture). These areas provide the oldest records and the oldest histories that can be mustered, boasting 186 groups inside of the Mikawa, Owari, and Mino regions. However, it should be noted that many of these groups have their own origin stories which are unique to them, varying from larger narratives. They are equally ‘valid,’ however, as they correspond with local historical development.

Farmer Army and Self Defense

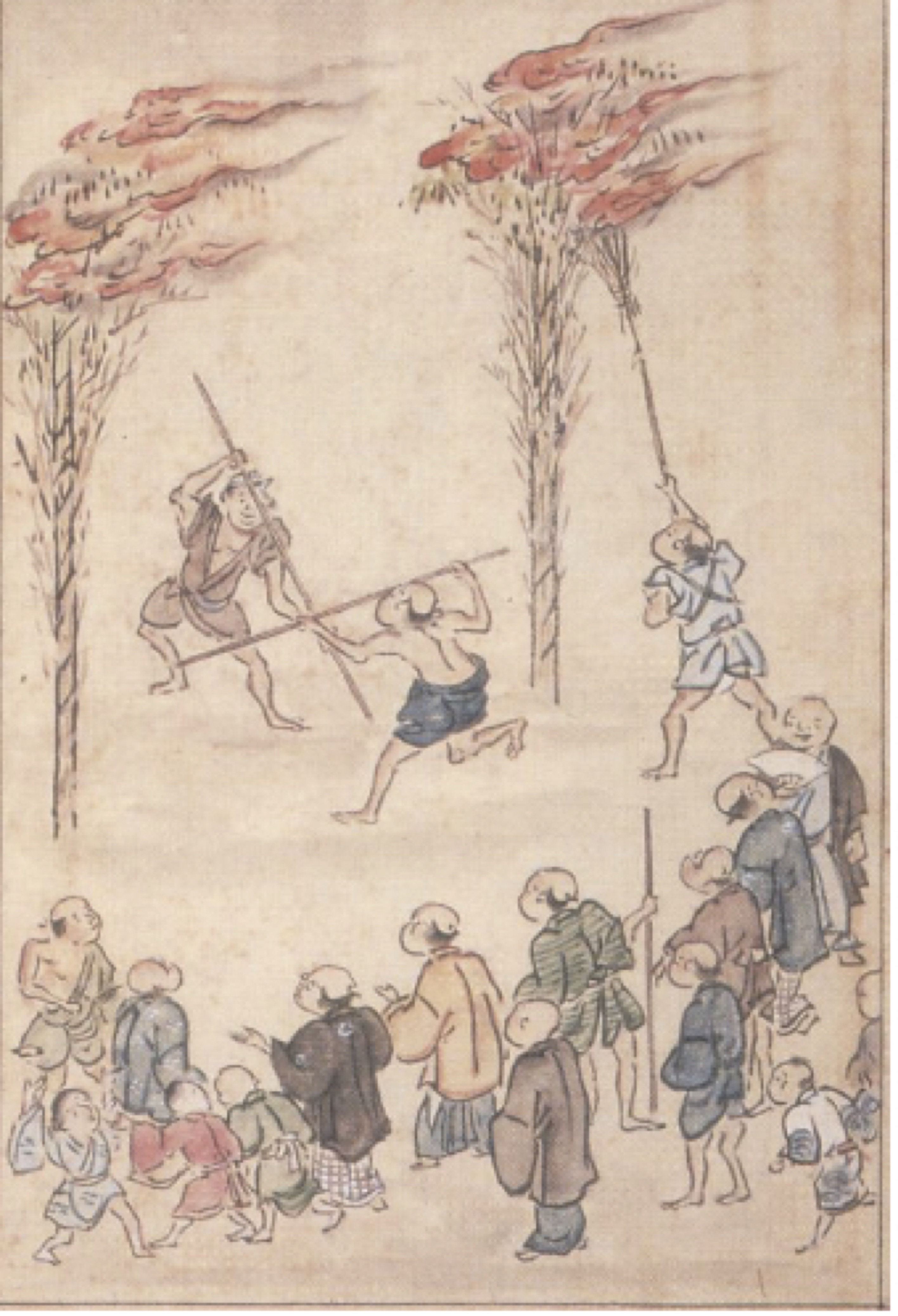

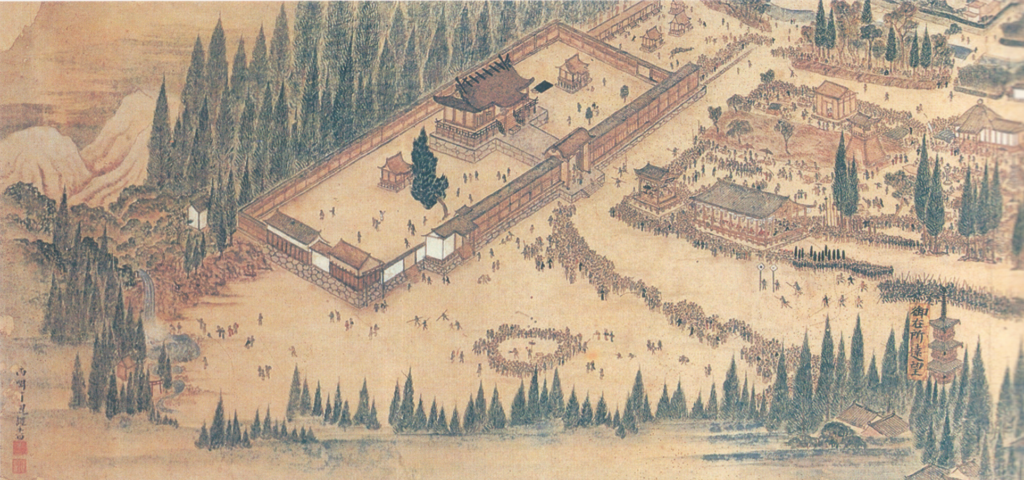

Mikawa legends say bōn ote began when farmers gathered yearly on Sanage Shrine grounds to create pacts, plan for the future, and to settle disputes once and for all. The latter commonly led to violence, which earned the gathering the title of kenka matsuri (‘brawling festival’). The spirit of bōnote arose from this meeting. Other towns from outside the area also attended, and they eventually created their own versions of the event in their villages.

ote began when farmers gathered yearly on Sanage Shrine grounds to create pacts, plan for the future, and to settle disputes once and for all. The latter commonly led to violence, which earned the gathering the title of kenka matsuri (‘brawling festival’). The spirit of bōnote arose from this meeting. Other towns from outside the area also attended, and they eventually created their own versions of the event in their villages.

It is said that the founders were bugeisha living in the area around the border of Mikawa near Owari (both now Aichi) and Mino (now in Gifu). They are believed to have organized the locals into groups and trained them to protect local land and towns. Two branches of bōnote, Kento-ryū and Kamata-ryū, are the largest and oldest out of twenty remaining schools. These two schools’ records keep other extinct schools’ histories alive; they are thus a direct connection to the foundation.

In 1471, within the Mikawa region of Japan, the third head of the Matsudaira family, Nobumitsu, extend his power by successfully overtaking Anjo castle. Over the next 50 years, their fiefdom spanned from the Yahagi River all the way up to their village above the Asuke River. Aligned landowners and warriors built rudimentary fortifications separated from the towns in the mountains and valleys. If attackers managed to overrun a town, these bunkers were in strategically advantageous locations where townspeople could take shelter. These structures were built and guarded by local warriors and landowners who had an interest in securing their town, so they were both manned and operated locally in the Matsudaira name. Bōnote experienced a rise in popularity during this time, and a wave of attraction followed as such fortifications become commonplace in the local culture in surrounding villages.

Then, in 1524, Oda Nobuhida had secured Owari province and pushed east into Mikawa. He forced the leader of the Matsudaira family at the time, Kiyoyasu, to fall back away from the Owari border east of the Yahagi River at Okazaki castle. When the military governors of Mikawa had left, peasants and farmers under the control of the Oda family were perpetually recruited to fight in local territorial disputes which continued for decades. It was here that Oda Nobuhida’s and later, Oda Nobunaga’s reputation of taking ordinary townspeople and transforming them into warriors was fully exhibited as locals were turned into what eventually became known as the ashigaru (foot soldiers). The weapons of the era were simple, and the wielders were assigned to groups or regiments that were then broken down into lines of attack; the most common weapon for the peasant warrior at the time was the spear.

As farmers were not professionals per se and they had jobs outside of warfighting and politics, they learned techniques that could easily be remembered, practiced, taught and transmitted within their ranks. In other words, the warrior-farmers would learn a bit of one school, a bit of another, go to war, and then take them back home to the farm and train when they were not tending the fields. When they were again called upon to join ranks and fight, those that had survived learned more and returned home to add to what they had.

As the methods of warfare and strategy advanced, groups of ashigaru were placed under the command of ashigaru taicho (‘foot soldier generals’) and preparations for battle became more sophisticated. Training and drilling spread and become part of the local culture throughout Mikawa, training parties were organized at shrines (the closest thing they had to public meeting facilities), and weapons were kept on hand and in storage. As a result, semi-autonomous guard towns and villages were created, which were prepared to meet attacks by rivals of Oda’s rule in the area if left without regular soldiers.

During this time, firearms were introduced to Japanese warfighting; however they were expensive to own and maintain, so they were kept locally by professional soldiers under the command of an armory. Despite this, firearms training did enter into regional practice; however, it was more centralized around armories and more controlled. The training was also different, more akin to taking up positions with unloaded rifles, aligning your sights/barrel to a target, setting your wick in the matchlock, and waiting for a loud bang (which could be done by an ashigaru taicho hitting something to make a loud noise, or just screaming “BANG”), mock reload and repeat. Even so, the main method of training in bōnote was for non-projectile ‘close to medium range’ weapons used by foot soldiers. Branch schools in remote areas of the region such as Nagisa-ryū, Sanage Kento-ryū, and Shikibu-ryū began to spring up, and bōnote flourished and spread like never before. Many consider this to be the golden age of the tradition and the height of its influence on local culture. After Oda Nobunaga committed suicide at Hannoji in Kyoto, theashigaru-turned-warlord Hideyoshi Hashiba took control and changed his name to Hideyoshi Toyotomi. He realized that the climb to power he made from a foot soldier to a page and then to a shogun could easily be made by other peasant-warriors. He, therefore, banned farmers from possessing weapons, and separated the warrior class from the farmers and merchants in one stroke with his notorious ‘edict on status changing’ law. The edict outlined three points: 1) foot soldiers could not return to their lives as farmers and townspeople; if they did they were to be labeled outcasts 2) farmers and craftsmen could not become merchants or engage in merchant jobs, and 3) soldiers who had deserted their posts under their former leader were denied access to any class.

After Oda Nobunaga committed suicide at Hannoji in Kyoto, theashigaru-turned-warlord Hideyoshi Hashiba took control and changed his name to Hideyoshi Toyotomi. He realized that the climb to power he made from a foot soldier to a page and then to a shogun could easily be made by other peasant-warriors. He, therefore, banned farmers from possessing weapons, and separated the warrior class from the farmers and merchants in one stroke with his notorious ‘edict on status changing’ law. The edict outlined three points: 1) foot soldiers could not return to their lives as farmers and townspeople; if they did they were to be labeled outcasts 2) farmers and craftsmen could not become merchants or engage in merchant jobs, and 3) soldiers who had deserted their posts under their former leader were denied access to any class.

This was all done to re-enforce the ideology of class separation under the threat of punishment, destroying any type of upward status climbing by limiting the mobility between castes. In theory, this effectively forbade the use of peasant-warriors as ashigaru. While this was the rule within Hideyoshi’s territories, it was apparent that many of his enemies and allies felt otherwise and did not follow his edict. This dissent grew stronger as Hideyoshi preoccupied himself with battles in Kyushu, and then, later in his attempt to invade South Korea. Much to his peril, his attempt to invade South Korea only with professional soldiers left him prey to the same winning strategy that Oda Nobunaga had used so successfully against professional armies in prior battles. What had once brought Hideyoshi up the ranks to a position of leadership was eventually the source of his problems in South Korea as he abandoned occupation of the Korean peninsula.

This was all done to re-enforce the ideology of class separation under the threat of punishment, destroying any type of upward status climbing by limiting the mobility between castes. In theory, this effectively forbade the use of peasant-warriors as ashigaru. While this was the rule within Hideyoshi’s territories, it was apparent that many of his enemies and allies felt otherwise and did not follow his edict. This dissent grew stronger as Hideyoshi preoccupied himself with battles in Kyushu, and then, later in his attempt to invade South Korea. Much to his peril, his attempt to invade South Korea only with professional soldiers left him prey to the same winning strategy that Oda Nobunaga had used so successfully against professional armies in prior battles. What had once brought Hideyoshi up the ranks to a position of leadership was eventually the source of his problems in South Korea as he abandoned occupation of the Korean peninsula.

Needless to say, bōnote‘s practice in the Mikawa area did not cease, despite Hideyoshi’s edicts. Mikawa was protected and under the control of Oda Nobunaga’s ally and reluctant disciple, Matsudaira Takechiyo. As Hideyoshi rose to power, the Mikawa area was handed over to Takechiyo, who was born under the name of Matsudaira in or around Okazaki castle. He lived through a strange set of events that included kidnapping as a teen, being held hostage by two families, and rising to power among his family’s enemies. This eventually led him to disassociate himself from his birth name, changing it to Tokugawa Ieyasu. With this new name, he managed to reclaim many of his family-owned territories and rose to power.

A Ward Against Evil

A contrasting narrative of bōnote revolves around shugendō, pilgrimages and the ‘protection’ the land and villages through ceremony and enchantments. While this seems straightforward enough, any real documentation on what went on during the early years of bōnote’s founding regarding shugendō is hard to find, because their practitioners, called shugenja, did not write down their histories or legends in a precise manner. Instead of documenting on paper, followers choose to pass on their traditions orally and physically as a part of a larger practice of austerity. This doesn’t mean that there isn’t anything written down, but what is chronicled is extremely esoteric, with little detail, and it requires an enormous amount of explication to understand. In many traditions, the oral practice and physical rites of shugendō is purposefully kept secret and mysterious, keeping outsiders from the tales by requiring an oath of silence by initiates. Likewise, it is said that there is hardly any written material regarding shugendō and the exposure of oral traditions is only known by ‘accident.’ The mountains and sacred sites are mystic and consecrated, and when practitioners leave them to traipse back to reality, they faithfully keep from discussing it to the outside world as illumination is taboo.

A contrasting narrative of bōnote revolves around shugendō, pilgrimages and the ‘protection’ the land and villages through ceremony and enchantments. While this seems straightforward enough, any real documentation on what went on during the early years of bōnote’s founding regarding shugendō is hard to find, because their practitioners, called shugenja, did not write down their histories or legends in a precise manner. Instead of documenting on paper, followers choose to pass on their traditions orally and physically as a part of a larger practice of austerity. This doesn’t mean that there isn’t anything written down, but what is chronicled is extremely esoteric, with little detail, and it requires an enormous amount of explication to understand. In many traditions, the oral practice and physical rites of shugendō is purposefully kept secret and mysterious, keeping outsiders from the tales by requiring an oath of silence by initiates. Likewise, it is said that there is hardly any written material regarding shugendō and the exposure of oral traditions is only known by ‘accident.’ The mountains and sacred sites are mystic and consecrated, and when practitioners leave them to traipse back to reality, they faithfully keep from discussing it to the outside world as illumination is taboo.

This meshed with the Edo era line of thinking, an era when Shugendō proliferated and attracted people from all social classes. What is known about the practice from that period is recorded in art and literature, where Shugendō tales and history appeared without explanation, presenting themselves as an oddity. For example, immersing yourself in water and trial by fire is known only because the spectacle was recorded by outsiders. If a person was walking along and stumbled across a group running through a bonfire, it certainly would be memorable. The same goes for water lustration and prayer rites; they are known only because they can be seen and recorded by people outside the tradition. However other traditions, such as jumping off and though waterfalls, passing through rocks as a ‘birth,’ entering sacred tombs, and a host of others are relatively unknown traditions that have only been exposed in the 19th and 20th century, with no real date as to how long they have been practiced. There are other practices that were ‘accidentally’ recorded and exposed outside of the oral tradition, many of which have now gone extinct. However, while what has been recorded and detailed is sparse, there are several groups who are much more open to talking, as modern-day culture has supported freedom of religious practice, something that wasn’t true in the past. Many groups still travel to mountains, go to sacred spots and carry on their traditions despite falling membership. As their popularity wanes, however, these groups are increasingly open to talking about and recording their activities, as they are aware that they may become extinct if they do not adjust to the times.

In the old Owari area (now Aichi), legends and local accounts tell of shugenja practicing and traveling through the villages and teaching, something recorded by the local bōnote groups. The traditional stories tell of shugenja teaching local farmers ‘sacred movements’ and techniques especially designed to scare off evil spirits and spread good fortune. These were disseminated within the schools of bōnote . To many in the old Owari area, this is the origin story of bōnote , related to defense and prosperity in the areas surrounding the grounds of Ryūsenji castle.

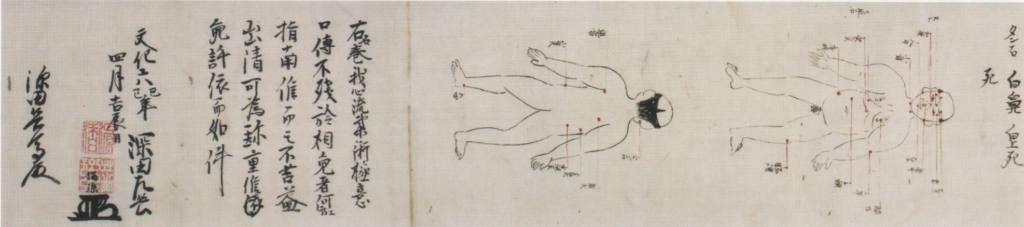

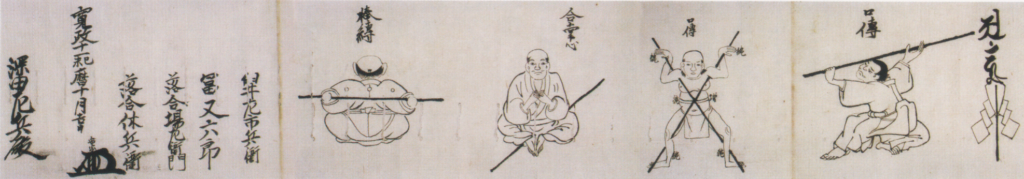

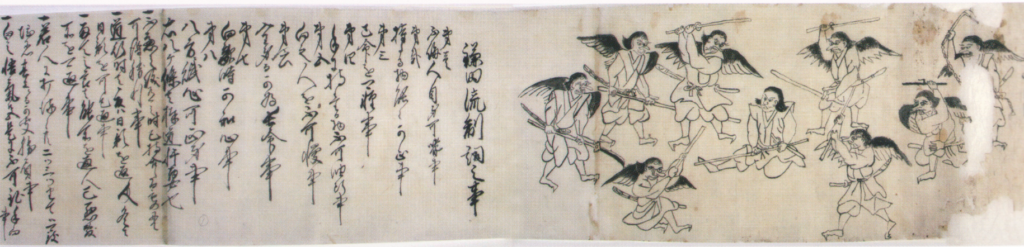

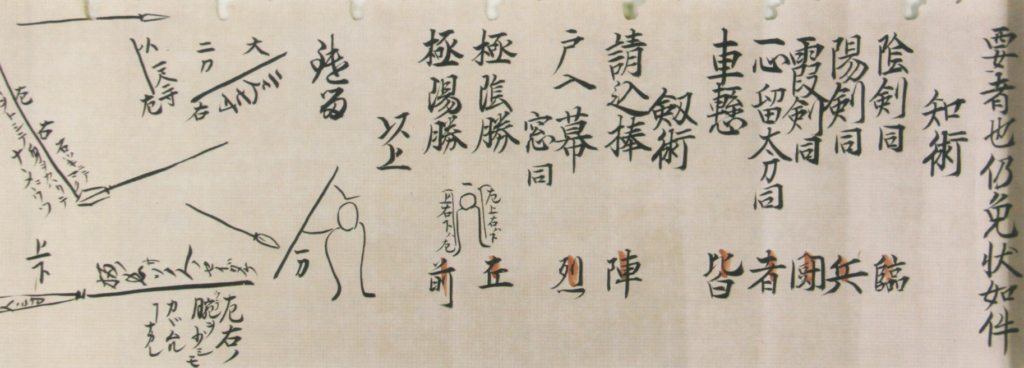

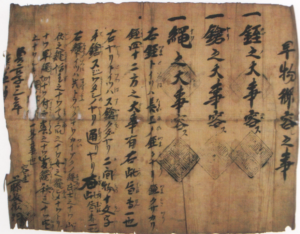

One of the major founding schools in the Owari region was called Muni-ryū, and although now it is technically extinct, it has a descendant school named Hissho Muni-ryū in Owari Asahi city that has preserved its records. The Ichikawa family in the Nisshin district of Owari Asahi possess old denshō and menkyō that attests to this foundation story regarding the influence of shugenja. In the menkyō, it clearly shows the names of the seven kata of Hissho Muni ryū with seven-winged mountain ‘elementals’ called tengu performing them: in particular, there is a heavenly crow apparition closely associated with mountain ascetics. The denshō illustrate and detail Marishiten Issho Hissho Ken containing the kata list, shugendō practices, and kuji-in (specific intertwining of the fingers [mudra] associated with chants [mantra]), all which came from branches of Mikkyō Buddhism that proliferated and spread in the area during bygone eras.

The founder of the school was named Ryozen. He was a member of the Sampoin group of the Tozanha Shugendō School under Daigonji (temple). He was given secret teachings by high ranking authorities of the temple, and awarded a menkyō (license) from them. He was also part of Sanjoko, a mountain pilgrimage group in Owari Asahi city that ascended Mt. Ominesan for religious rites, believing that a powerful deity dwelled there. This group, the secret teachings, the Sankojo group and the ascension to the mountain are all interlinked, and were a primary tool for spreading bōnote in the Ryūsenji area, along with the spread of Tozan-ha Shugendō throughout the districts. It also forms a recorded connection between pilgrimage patterns in the area, religious ceremony at the local shrines, all focused on the spirit of Mt. Ominesan and Shugendō. It was this connection to local shrines, the pilgrimage trail, and the community that has preserved the record of what the shugenja of the area were up to. This should not be considered an official record of the religion, but a kind of side note that exposed much of the history and tradition that they founded in the area, almost by happenstance.

There is some disagreement concerned whether the teachings of the shugenja were blended with bōnote traditions that existed prior to their appearance, if the traditions developed mutually within the era, or that the foundation of Shugendō and Mikkyō practices were at the core of bōnote from the beginning. Not only is there is no clear or decisive answer, there are many opinions that accompany the information, each having a plausible narrative, yet all equally indecisive in their conclusions. What does bind all of these groups together is local practice and ritual. While they differ in their approaches and history, they form a woven cloak of local tradition that prevails to this day in practice.

Cultural Shifts

After the battle of Sekigahara, the regional wars and infighting eventually came to an end. Tokugawa Ieyasu must have seen the same merit in the established tradition of bōnote in Mikawa that his mentor Oda Nobunaga did, and he allowed it to continue under his rule as a “shrine dance and ceremony.”

After the first half of Edo, however, the ashigaru armies were no longer needed. Given that a caste system was implemented by the military government under Tokugawa, those who had a background as a soldier moved on to fitting into one of the peasant castes or became bushi. Nonetheless, bōnote continued on throughout the Edo period as a fundamental part of village life, unencumbered by local government. Some say this was due to favoritism to the area as it was the ancestral home of the Tokugawa family; others say it was typical of the era to turn a blind eye to peasant training disguised as ceremony.

Whatever the case, a hint to the purpose of bōnote during this era comes in the form of an old saying associated with the practice: umano to ni bōnote wa tsukimono (‘a pole to dedicate a horse’). This alludes to the performance of a shrine ritual to protect new horses in the village, as well as bōnote as rites of the village, not only to guard the horses, but to dedicate the ‘staves’ used to guard them and the village. In this sense, mixed with shrine dedication, the horse ceremony and bōnote became inseparable to protecting the village. It was also during this era that changes in bōnote were recorded, with groups changing and reforming, varying from the original ryūha. They kept the same basic movements, but added slight variations and alterations as time passed. These slight modifications built up over time, changing a little bit in one year, then a little more the next, adding a variation or new set as they went. Categorization of the kata (‘pattern drills’) became common, and stick and wooden sword techniques became known as omote (‘front’ or ‘outside’) and techniques where shinken (live, steel weapons), naginata (glaive) and yari (spear) were used were labeled as ura (‘back’) or kiremono (‘cutting things). In some areas they call this hanabo or kabo (‘flower stick’) in contrast to the others.

In the Edo period, although weapons were not allowed to be owned by individual villagers other than bushi, the members of bōnote actually had an armory of shinken in their possession, kept by the shrines and community for use in bōnote . This was rationalized that because it was a sacred religious ceremony dedicated to local deities, live weapons were acceptable. Contrary to the laws insisting weapons were not to be owned by peasants, the bakufu law was, in effect, suspended. Demonstrating with the live weapons was more popular and common than the omote. In fact, it became more of an act of daring to demonstrate with live weapons, adding thrills to the event and a spirit of fear mixed with excitement that drew crowds. Because of this, more live weapons were added to their roster, and more techniques along with them. It has been speculated that they borrowed techniques from local bugei (martial arts of the warrior class) in the Owari area to fill in the gaps of knowledge with their new weapons, and brought them back to the bōnote groups under the platform of a ritual.

In the Edo period, although weapons were not allowed to be owned by individual villagers other than bushi, the members of bōnote actually had an armory of shinken in their possession, kept by the shrines and community for use in bōnote . This was rationalized that because it was a sacred religious ceremony dedicated to local deities, live weapons were acceptable. Contrary to the laws insisting weapons were not to be owned by peasants, the bakufu law was, in effect, suspended. Demonstrating with the live weapons was more popular and common than the omote. In fact, it became more of an act of daring to demonstrate with live weapons, adding thrills to the event and a spirit of fear mixed with excitement that drew crowds. Because of this, more live weapons were added to their roster, and more techniques along with them. It has been speculated that they borrowed techniques from local bugei (martial arts of the warrior class) in the Owari area to fill in the gaps of knowledge with their new weapons, and brought them back to the bōnote groups under the platform of a ritual.

Another notable change is that, with the addition of new weapons and pre-arranged forms, the seminal versions of the kata were altered dramatically from the originals and theatrics were added, accompanied by ‘play-like’ storylines that could be followed in order to please the crowd and engage their interest. It is here that comedy was added to the kata, along with narratives being performed, in some cases accompanied by silly costumes. While this made bōnote more popular, it took study time away from the original techniques of the school. Then, as the popularity of the most traditional techniques waned and faded in favor of crowd-pleasing dramatics and comedy, many of the old original techniques were abandoned. Some of the most important kata were lost or forgotten as older members died, and among others that remained, some were misremembered. Ultimately, because of lack of interest, there was no one left to pass on many bōnote traditions.

The loss of these traditions has been a concern for a long while; however circumstances have changed. Lack of interest is no longer to blame these days; rather, there are fear and safety concerns. For example there is a technique that originated in the Tanuki of Bisai city called kakegiri. It involves a jutte (truncheon) and stick of bamboo against a live sword. After the bamboo is cut twice by the sword, the practitioner discards the bamboo and grapples with the opponent (kumiuchi). While still performed by some groups and drawing a great amount of attention, a group in Sakurai-cho in Anjo altered it in 1989. In the original unaltered form, practitioners with a live sword would cut thick pieces of green bamboo held by the opponent in a defensive position, but safety concerns forced them to replace the sword with a wooden staff and the thick green bamboo pole was replaced by a dry, thin piece of bamboo. Rather than cutting, the bamboo was broken with the staff. Although not totally gone, this technique has changed to a mere shadow of its former self. By the mid 2000’s, even the altered form was deemed too dangerous, and kakegiri has been completely abandoned. It is in this way that bōnote has been whittled away at over time, changing little by little, becoming something other than it once was. On the other hand, it could be said that this has always been typical of bōnote , as the changes are a way to keep it alive, despite the times and cultural shifts.

Modernity

During the Meiji era and the cultural reforms that it brought, bōnote was considered part of the old ways, a reflection of the Edo-period caste system. Thus, it was relegated to being banned and forgotten during the struggle for power between the forces of the new emperor against the Tokugawa shogunate. As war between these parties progressed, many of the bōnote practitioners were sent to war; however, their spears and other weapons used for bōnote were collected and melted down to be recycled for rifles and cannons.

Nonetheless, the practice did not cease; its ceremonies were maintained behind closed doors under the blind eye of a government struggling to gain power. The secretive nature of the rituals adapted to the times; however, this was not without consequence. Preservation of the tradition was successful, but many of the schools that had existed for centuries went extinct as members were killed and the population lost their youth to war. Not only did this limit the number of schools, it also limited the number of new members as bōnote was kept tucked away outside of the prying eyes of outsiders.

It was only after thirty years into the Showa era that bōnote could show its face again. The areas that had practiced in secret revived their festivals, mostly due to the nationalist push by the Showa government, and the enactment of Kokka Shintō (‘State Shintō) in Japan. This was done under the attempt to consolidate all folk practices under one national banner. Once again, bōnote went public, this time adding a performance element into their efforts to please the crowds and inspire the nation. It became a local attraction, inspiring tourists to show up and contribute to the local economy via tourism under the guise of national pride and vigor.

In Showa 30 (1955) the ‘Cultural Treasure Act’ was bestowed on the remaining bōnote groups, which sparked the forming of the ‘Bōnote Preservation Association.’ This meant local government funding and support would be given to the remaining groups in an effort to keep them from going extinct, and from that, four main groups sprang up: Yasura no Bōnote (Konan City); Nagakunote no Bōnote (Nagakute city); Sakura no Bōnote (Nagoya City) and Ogita no Bōnote (Kasugai city). Soon after, in Showa 31 (1956) the four groups were given the status of ‘Intangible Cultural Assets’ by the prefecture. Several years later, thirteen more groups formed to preserve the bōnote heritage in their areas, the last of which was the Sakuraicho no Bōnote (Anjo city) in Showa 39 (1964). They too were designated as ‘Intangible Cultural Assets.’ Despite all of these efforts, many of the schools and associations still lost members as local people moved from the countryside to the city, leaving their old life behind for the promise of office work and big city life. Thus, membership dwindled. Many schools had no successor to pass the traditions down, leading to the demise of many of the associations. It became hard for these individual groups to survive on their own, so they ultimately consolidated the groups into a collective preservation society. Even so, adult participation is far lower than before as office life has superseded farm and craftsman life. These days, children and young adults have become the main focus. In this era, it is questionable if bōnote can be preserved, as the environment and lifestyle has changed far too much for it to continue. As is with all folk traditions, only time will tell.

References

- Special thanks to the staff of the Toyota Bōnote Kaikan museum staff for supplementary information regarding the details of this article

- Thanks to Shunya Suzuki for providing source materials and directing me to where to find them

- And credit to the book, Sakuraicho no Bōnote Umanoto and other contributors who wish to maintain their privacy for extensive and detailed information used in writing this article.

No part of this material may be reproduced in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, without permission in writing from the author. However, you are welcome to share a link to this article on such social media as Facebook, LinkedIn or Twitter.

Rick Matz

Fascinating history. Thanks!

Richard Lewis

That was a great read, many thanks.

Alexey Markov

Excellent essay!

There are echoes of bōnote in Katori shintō ryū. This is mentioned in their denshō “Katori shinryo shintō ryū kongenshō” (香取神慮神刀流根元鈔).

Yancy Orchard

Fantastic read! Great historical detail, and I really appreciated the analysis and commentary. Thank you.