By Nigel Sutton

Note: During the writing of this piece Master Lee Bei Lei passed away. He was 86 years old. Rest in Peace, Shifu!

I first met Lee Bei Lei (aka Li Bian Lei/Lai) in 1987 on my first visit to Malaysia. My brother-in-law was secretary of the taijiquan group that he ran in Batu Pahat, a town in the southern state of Johor. As a ‘visiting fireman,’ who had participated and enjoyed some success in a competition in China, I was invited to perform in front of an audience of several hundred taijiquan aficionados. At that time Chinese in Malaysia were not allowed to visit China, so a foreigner who had been there and practised Chinese martial arts was something of a rarity. I strutted my stuff, the 48 step combined taijiquan form and a baguazhang form and afterwards, I was introduced to ‘The Master,’ Lee Bei Lei. My youthful naïve ignorance protected me from even being aware of the dread I should have been feeling. I had come to his training hall as a ‘celebrity,’ demonstrated in front of his students and basked in their applause! A traditional martial artist of Master Lee’s generation would see all of this as a challenge, literally an attempt to damage his reputation. This to a man for whom challenges were an everyday occurrence, the very lifeblood and nourishment of his existence! But I knew none of that.

When he was introduced to me by my brother-in-law, I saw a huge man for a Chinese, with a very upright stance and a face full of amused disdain for me and all that I represented. He offered me a huge index finger and asked me to grab it and bend it. I took the digit in my fist and strained with all my might, but I could not move it. Then, by seemingly just wagging the finger from side to side he was able, with ease, to disrupt my balance and move my whole body from side to side. He then instructed me to strike his stomach with my extended fingers, and with a dramatic expansion of what was already a quite substantial belly, he not only intercepted and nullified my strike, but also caused me some degree of pain.

This was not the first time that I had encountered the famed neigong methods of the Malaysian Zhengzi taijiquan school, and I was already sold. The various demonstrations–taking blows all over the body, being hit by telegraph poles or having chairs smashed over the back–were all impressive. What impressed me more, however, were the fighting exploits of the students of this style and the martial reputation of the school. These were men (and in rarer cases women) who walked the walk. Their taijiquan was a fighting art: this was what I wanted to learn.

Over the next few years, I became initiated in the Zhengzi lineage and learnt the neigong (internal strength) exercises that were the ‘inner teachings’ of the art, available only to those who had undertaken the formal baishi ceremony. I learnt these exercises from several different teachers. Although all of whom taught them slightly differently. the fundamentals were identifiably the same.

Each of the major teachers I learnt from had been drawn to Zhengzi taijiquan in the same way; already established as teacher or master-level exponents in other arts, they took part in challenge matches against a Zhengzi taijiquan exponent and were defeated. This, in every case, prompted them to do the gentlemanly thing according to the code of martial ethics, and become a disciple, if not of the man who defeated them, then of his master.

During my training time with these teachers I periodically encountered Master Lee, once at a competition where, unhappy with a refereeing decision made against one of his students, he challenged the panel of judges to a fight. These judges, all of them ‘masters’ in their arts, kept their heads down and would not meet his gaze, let alone his challenge. His outrage was vindicated when the committee that adjudicated such matters reviewed the referee’s decision and overturned it. Master Lee’s student went on to win the championship.

On other occasions, I was delegated to take visiting students from the UK to his club to engage in pushing hands bouts with his students. He was always polite and his students were welcoming but he never resisted the opportunity to ‘strut his stuff,’ to show the foreigners in general, and me in particular, how little we really knew.

Each of my teachers, although from the same lineage, approached the art in an individual manner. They always justified this with the claim that the way they practised was the unique way, taught to them alone by their teacher. There came a time when Master Lee and his teaching became the focus of my study. Given that I knew of his exploits as a fighter, why had I left him to later in my studies? The reason was that amongst the more ‘refined’ members of the Malaysian Zhengzi community, his reputation was that of a crude and unrefined brawler. On the whole, taijiquan exponents pride themselves on the fact that their art is many levels raised above the ‘brute force and ignorance’ of other systems. At that time, it would be fair to say, my view of the art was not uncoloured by this elitist attitude.

Nevertheless there was no denying that Master Lee was a successful and very visible exponent of the fighting arts, and his art, as he loudly and proudly proclaimed, was taijiquan. Eventually, I made an approach to ask him to take me as an initiated disciple. This was facilitated by my brother-in-law’s continued service as club secretary and the fact that Master Lee had met me on a number of occasions over several years. His answer, however, was not immediate. In fact it was several days before I got a reply, in the form of an invitation, to visit the house where Master Lee was staying together with a number of his students. At that time they were all in the southernmost city of Malaysia, Johor Bahru, to attend a national level competition. My wife and I also happened to be there as she was also taking part in the competition.

The ‘entering the door’ ceremony took place at this house and gathered there as witnesses were many of Master Lee’s senior disciples and peers. Afterwards I was given an immediate taste of Master Lee’s unique style and the training methods he used. After engaging in a very short but painful ‘sparring’ session with my new mentor, I was immediately taught the first of his series of internal strength exercises.

At this juncture, it is worth considering just what the nature of internal strength training is within the Malaysian Zhengzi system, and also what it accomplishes. Historically, it is traced not to the Yang family, with whom Zheng Manqing most notably trained; but to Zhang Qingling, who although also a Yang family disciple, was in addition a member of a daoist lineage of internal martial arts. These he had learnt from his teacher, Zuo Laifeng. Within Zhengzi taijiquan, they are referred to as the ‘Zuo method.’ The effect of this training is to enable the exponent to receive force from an opponent and neutralise it by diverting the incoming power into the ground. At the same time s/he is able to take this force from the ground and return it in the form of devastatingly powerful counters. This is described in the taijiquan maxim: “Neutralising is striking, striking is neutralising.” This training also enables the practitioner to use timing and distancing to render the opponent’s attacks ineffective, while magnifying any counter delivered. In addition, there is an emphasis on the development of tactile sensitivity at grappling range, which allows the exponent to be constantly unbalancing their adversary thereby making strikes even more devastating. The student of taijiquan also learns how to both ‘segment’ their body into various parts, in order to disguise their own centre of balance and gravity, and then how to reunite it in a whole so that the sum is much more powerful than the individual parts. This is described in another maxim: “In taijiquan there is no fist, the whole body is a fist.”

Training consists of several sets of standing and sitting qigong (‘breath/energy skill’), combined with pai da gong (‘slapping and striking skill’). The latter are self-striking exercises designed to condition the body. In addition, there are also a number of exercises designed to stretch what we would now refer to as the fascia, training exercises involving breath and sound, and various meditative practises, some involving the circulation of qi (‘vital energy’) and some not.

While the majority of these exercises were (and in some cases still are) kept secret, others are openly taught in other martial arts systems and schools of spirituality and meditation. Knowing these exercises, alone, however, is not enough. They have to be practised rigorously; in the first case for a minimum of 100 days. The full set of exercises which are supposed to be practised twice a day during this period, takes at least 90 minutes of training. Like most good things, especially when developing what the Chinese call gong fu, this is boring, repetitive and not without pain.

Furthermore, just developing the gong fu of these exercises is still not enough. Many other martial systems have the same things, but they can only be used when the taijiquan body has been created and the strategies and tactics of the art have become firmly embodied.

The shenfa (body method) that Master Lee taught was no different from any other teachers in the Zhengzi school with whom I had trained. There were, however, differences in emphasis. The first was the insistence that the body should be made as strong as possible through specific exercises. While strength of the physical body was always important in the early stages of taijiquan training, Master Lee’s differ in that the limbs all had their own specific and rigorous training regimen.

- The hands are trained with an iron ball in a combination of gripping, throwing and catching exercises, supplemented with ‘rolling’ the ball on a tabletop using the four key directional energies of peng, lu, ji and an (expanding upward and outward, moving backward around the body, moving forward and moving down respectively).

- The arms and the forearms in particular are drilled with a series of exercises involving clenching and unclenching the fists while the arms are outstretched. These yang exercises are balanced by swinging the arms in various directions motivated by turns of the waist, providing training in the development of both centripetal and centrifugal force.

- The legs are trained by an exercise that Master Lee called ‘Fair Lady’s Leg,’ a tongue-in-cheek reference to the famed ‘Fair Lady’s Hand’ position which is one of the signatures of Zhengzi taijiquan. This exercise involves a particular method of walking straight-legged with the toes raised and the weight resting on the heels which develops strength in the lower legs.

- Another aspect of Master Lee’s internal strength training was the use of a staff. There was no set form, only a series of basic movements and two-person applications. The use of the staff acts both as a ‘force multiplier’ and also teaches how to use the whole body to deliver strength to the very end of the weapon. When this can be done successfully, the exponent finds that their ability to exert force unarmed is greatly improved. The key teaching here is: “Power is rooted in the feet, developed in the legs, controlled by the waist and expressed in the hands.” (NOTE: Although staff/spear thrusting and shaking is a major part of our training in many factions of Zhengzi taijiquan, this was not Master Lee’s emphasis. He focussed on the rolling of the wrists, often one against the other (something like the shibori (‘wringing’) action in Japanese sword schools) and the development of sensitivity and power through sticky staff exercises – like pushing hands with spears. I should also note that Master Lee always described Donn Draeger’s sensei’s staff work as the best he had ever seen!)

In order to really understand and be able to effectively use this teaching one has to engage in systematic and detailed pushing hands practice. The ‘root’ can only be felt when someone attempts to disrupt your balance and a clear line must be created between the incoming power and the ground. This means that the body must be aligned so that power flows through it, without any points of resistance or unnecessary tension.

Where Master Lee’s methods differed from other teachers in the Zhengzi lineage was in that, in addition to identifying and training the development of ‘clear pathways’ for incoming force, his students also practise deliberately making things difficult, by ‘breaking’ their body structure, and then attempting to regain it as efficiently as possible. This might mean, for example, that instead of keeping the head erect, as if suspended from above, one allows it to ‘loll’ around. A similar method of making things more difficult is to raise the heels off the ground so that one uses only the balls of the feet to ‘root.’ A unique way of doing this, used by Master Lee’s students, was to saw traditional Chinese wooden clogs in half and then to wear them when doing either their form or pushing hands practise.

The training process in Master Lee’s school places constant emphasis on repeated practise of the basics. One often hears the refrain that there are no secrets and that the only secret lies in mastery of the fundamentals. In both my experience and that of the long-term students of the school this certainly has proven to be the case.

While Master Lee did not stress form (37 posture of Zheng Man Qing), he did insist that his students should practise it enough to come to the point where they could identify those important aspects that were essential to effective usage of the art. These aspects are almost all related to body structure, as described above. Once this is done, the student is able to make the most effective usage of the pushing hands practice to test and reinforce their progress. Similarly, through staff practise, both solo and with a partner, shenfa is further reinforced and tested.

His willingness to put his art to the test was legendary. Students and peers tell tales of him accepting challenges in crowded coffee shops, outside his front door and at the training hall of rivals. He worked as a tour guide for much of his life, and wherever he went, he would also seek out fellow martial artists to put his art to the test. Such an attitude is also part and parcel of the developmental process in learning and refining ‘internal strength.’

One common story that you hear from those who were to become the Masters of Master Lee’s generation, and from their students as well, is that the basic training was so physically tough that they were unable to walk up or down stairs or squat on the toilet. Another thing that all of these accounts have in common is the fact that the period of basic training, although intense, was not long. The figure constantly heard was two years. After two years of such training, those who still felt the urge to continue on the path, were encouraged to enter the martial world and teach. In the traditional Malaysian Chinese martial world of that time, this of course meant that they were open to challenges. This, in turn, signified that their Master had confidence in their skill and had o worry that they would disgrace his name or that of the school by not constantly proving the supremacy of their art.

Master Lee Bei Lei (Birth name Li Mu Guan) was a true giant of his generation and he set an example for all of us, his students, to follow. No bow of respect, no words are deep enough to convey the debt that we owe to him. All we can say is that it was a privilege, it was an honour, it was real!

Photographs Courtesy of Michael Belzer

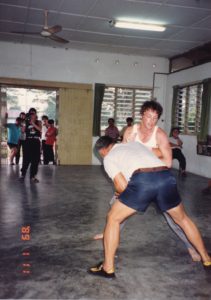

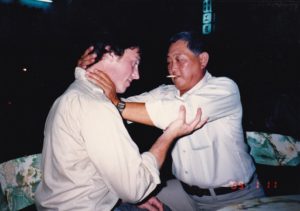

NOTE: Michael Belzer first met Lee Bei Lei in 1979, while traveling with Donn Draeger (see picture on left). In the 2nd picture on top, he is demonstrating a counter-attack using his fingers, which people describe as being roughly the same size and strength as railroad spikes. Ten years later, Belzer went back to Malaysia and visited many of the teachers he’d previously visited with Draeger. Lee, of course, invited him to spar, which, as the pictures show, ranged from moments of dynamic equality, matching strength and skill, to moments . . . less so.

No part of this material may be reproduced in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, without permission in writing from the author. However, you are welcome to share a link to this article on such social media as Facebook, LinkedIn or Twitter.

Purchase Nigel Sutton’s Books Here

Purchase Ellis Amdur’s Books On Budo & De-escalation of Aggression Here

Ellis Amdur

The following is an account of Michael Belzer’s various meetings with Lee Bei Lei, whom he first met in the company of Donn Draeger in 1979. Michael has kindly permitted me to splice together our correspondence of several emails, as a follow up to Nigel Sutton’s blog.

In 1979, Donn and I met him for lunch in some village on the mainland. The food was excellent and after we ate, Master Lee grabbed my hands, looked at them closely and then said “Baby hands. You have done nothing.” Sigh.

Then Donn said, “You can attack him anyway you like. He has promised not to hurt you.” Soooo, at this point, he was sitting off to my left at about a 45 degree angle and his right arm was resting on this right leg. I made a grab for his elbow and wrist, attempting a ‘gooseneck’ wrist flex. The feeling I had was that he ‘melted away’ from my grip, stood up and with his right shoulder , he ‘bumped’ me into my sternum. I flew back and was headed for a bike that was parked inside the cafe. He swooped in with his left hand and caught me around my back. “You, O.K., You O.K.” is all he said to me.

The techniques that he was showing on me in the photograph above (top right) is one of many that were all finger strikes. According to Donn, he could smash a cinder block with a back hand of his fingers! That is something I would have to actually see, but if Draeger said it, then he saw it.

Ten years after my ’79 trip with Donn, I decided to go back to Malaysia and see if I could search out all of the teachers he had taken me to. I wanted to say hello, pay my respects and ask them more about their own experiences with Donn.

The day I spent with Master Lee was a full one. During the day he brought me to an open air gathering area and he put out the word that I was there (with my girl friend, Diane). He brought in a gal who was the translator for us. Master Lee had several of his students demo some two man drills and then he asked me to come up and ‘try some stuff’ (all of which he dissolved easily).

Then the translator said “Now, he want to fight you.”

Sigh. (Gee, how is this going to end up?)

“Well”, I said, “I won’t fight you, but I would like to do some friendly sparring with you. Would that be O.K?” He smiled and said “O.K.!” One of the pictures on the lower left above shows some of that tussle–the other shows Master Lee demonstrating the strength of his dantian.

Later that evening, Master Lee invited us for dinner and afterwards we got in some more training.

I think my favorite pic is the cigarette in the mouth/choke attack. ☺

The other pictures is the last of three that show me trying to push him and then he sends me flying backwards over a bed. You can see he was having fun with that one.

After I got back from my trip to Malaysia in 1989, one day I received a phone call and on the other end of the line I heard “Hello, Mr. Mike. It is Master Lee.” Quite surprised to be hearing him on the phone, I said “Master Lee, Good to hear from you! Are you here in the U.S.? He said “Yes, I’m at Disneyland.”

Wow. Turns out here was part of a group tour to the U.S. and one of his stops was Disneyland. He asked if I was free and could come to the hotel he was staying at. I said “Of course!” and made the drive from Santa Monica down to Anaheim. He was staying at a hotel nearby the park. While I was there I asked through a translator what his schedule was and found out he would be in town a few days. So, I invited him to come to the Inosanto Academy where I was teaching a Friday night ‘Cement Jujutsu’ class. I put the word out that one of the master teachers that Donn Draeger took me to see back in 1979 was here in the U.S. and would be the guest instructor at our class. We had a good turnout and Master lee demonstrated his style of taiji with some solo forms and then asked for volunteers to come up and ‘feel it’.

It was a great night of training and sharing and I will always remember how well he treated me and shared his knowledge of the martial arts.

Ellis Amdur

In a recent interview (2020), Dan Inosanto was asked about Master Lee’s visit. He said, “Oh my god, that guy was so strong! I wish I could have spent some time learning from him . . . “

Andrew Shinn

Fascinating piece! I have a dim memory of reading about Malaysian tai chi circles before, and by all accounts they were fighters!

What really struck me in the above was the following:

“Another thing that all of these accounts have in common is the fact that the period of basic training, although intense, was not long. The figure constantly heard was two years. After two years of such training, those who still felt the urge to continue on the path, were encouraged to enter the martial world and teach.”

Now that’s something! Two years to “mastery.” And of an “internal art” no less. If true, there are a lot of people spending far too much time on the essential skills out there…

Keni Lynch

Hi Nigel, this was nice to read. I was glad to hear of the internal practices, rolling a ball on a table, Fair Lady’s Leg, clenching and un-clenching the fist in an internal manner, staff training, etc. Funny thing is, despite not getting the internal (at least not explicitly in inner-circle training… I had to move to another city in a hurry to continue my uni education..!), I came to a point in my understanding, a few years ago, that I recommend such things to my own students now. I am very glad to see that my intuitions were right. It’s really nice to see them confirmed here. This just goes to show that it is possible to teach ourselves (inwardly, meditatively) by asking what the forms mean, and we will all eventually get there on our own, even without explicit instruction (although, I am also willing to concede that I may be the odd man out, a uniquely obsessive student in the Huang Sheng Shyan lineage: 18+ years. Thanks once again for writing about your experiences with Master Lee. 🙂