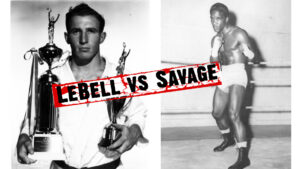

Some time ago, Ellis Amdur asked me if I’d be interested in contributing a guest post for the site. Knowing of my friendship with the renowned grappling expert, “Judo” Gene LeBell, and aware of Gene’s past relationship with the famed budoka, Donn Draeger, Ellis thought I might be able to offer some of Gene’s recollections to provide a different-than-usual take on Draeger, and the martial arts of a bygone era.

While Gene’s memory for details has faded a bit with time, I’ve had a number of extensive conversations with him in the past for various magazine articles, not to mention an aborted collaboration on his first attempt at an autobiography years ago. So I’m probably as qualified as anyone to share his impressions on these matters.

As far as Draeger goes, Gene always spoke very highly of him. “A great judo man” and “the best with weapons” was how he described Draeger to me on one occasion, opinions which probably won’t surprise anyone familiar with Draeger’s career in the martial arts. A generation older than Gene, Draeger came out of that pre-war school of judo which the early Japanese instructors in the West employed. My sense of that type of judo, both from talking to Gene and my own research, is that it was a somewhat more combative style, one laced with a bit more groundwork than would come to be the norm in the postwar years. That’s the style Gene appreciated, and I think he respected that “hardcore” approach in Draeger’s style.

The admiration was apparently a two-way street as Draeger expressed his respect for LeBell’s skills in letters to his longtime collaborator, Robert W. Smith. On one occasion, when Gene was scheduled to come into Tokyo to referee the infamous boxer vs. wrestler match-up between Muhammad Ali and Antonio Inoki, Draeger wrote to Smith that, while he thought the bout itself would be a farce, he was looking forward to getting a chance to visit with LeBell.

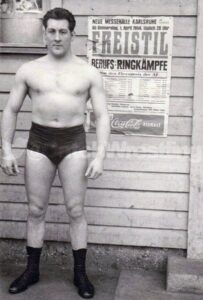

Draeger went so far as to offer the opinion that the best man in the ring that night would be Gene, who could take either of the two headliners in a fight. As an interesting aside, one of Inoki’s cornermen for the match was legendary catch wrestler, Karl Gotch, known in Japanese pro wrestling circles as Kamirasu, “the god of wrestling.” Years earlier, Gotch had been one of Gene’s main grappling coaches and, while Draeger thought Gene could take either Ali or Inoki in a fight, Gene once commented to me that what no one watching the match realized was Inoki’s cornerman, Gotch, could have taken both men at the same time!

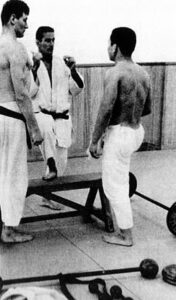

On an earlier occasion, around sixty years ago, Draeger spied LeBell training at the Kodokan and told his then young protégé, the now deceased Dutch judo and karate great, Jon Bluming, to go over and work with Gene because he could learn a lot from him. Draeger, who, with injuries and age, was turning more and more toward a groundwork-oriented style of judo, was clearly aware LeBell sometimes enjoyed using catch wrestling holds on the judo mat which could generously be termed “non-standard.” But apparently he had no problem with LeBell’s approach to the art. For his part, Bluming, too, saw the value in what Gene had to offer, maintaining their relationship for many years, occasionally traveling from Holland to Los Angeles to continue training together.

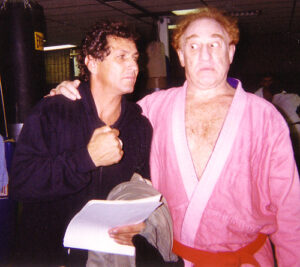

What may seem unusual to some who are vaguely familiar with the careers of both Draeger and LeBell is that two men who were, in many respects, polar opposites had such respect for each other. Draeger could be considered the father of the traditional koryu movement among more conservative-minded martial artists in the West. Though I’m told he had a good sense of humor and was not as dry or buttoned-down as his books would lead some to believe, by most accounts he was still a quite serious and notoriously private individual.

Gene, on the other hand, came out of the pro wrestling/Hollywood showbiz world. He used to show up at the Kodokan with his gi dyed bright pink just to get a rise out people. He never had much use for tradition, and any readers out there who are traditional martial artists themselves really don’t want to know his thoughts on kata.

Nevertheless, LeBell and Draeger both seemed to hold enormous respect and fondness for each other. The reason, I suspect, is something Ralph Mitchell, an American pioneer of traditional kung fu who, nonetheless, enjoyed cross-training in arts like muay Thai and was an enthusiastic supporter of mixed martial arts, once said to me, “A real fighter loves another real fighter.”

Whatever else you want to say about them, both LeBell and Draeger were real fighters, alpha-male types who knew what it was like to get into a good brawl and had no qualms about taking an opponent, and, as Gene would say, “making them squeak.” And both were near the top of the heap when it came to fighting. Perhaps, if they’d been of the same generation, their relationship would have been more competitive, and thus more antagonistic, the way Bluming and fellow Dutch judo great Anton Geesink’s relationship was. But the two men were at different points in their careers when their paths first crossed and Gene could admire a respected fighter from the same generation as many of his own teachers, while Draeger, perhaps, saw some of his old self in the younger man. I think they could probably put aside any philosophical or personality differences they had because they recognized the other man had the one thing that counted most to both of them – they could each kick ass.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.