Japanese martial arts, as codified systems known as ryuha was developed in the Edo Period (1603 – 1868 CE). Also known as the Tokugawa era, this was perhaps the most successful totalitarian state ever developed. Through an elaborate system of checks-and-balances, the Tokugawa family, in the role of shogun, ruled a vast archipelago, comprised of separate feudal domains. Unlike Europe, they were able to maintain this essentially feudal federalism even with the rise of an economy based on the capitalism of the merchant class.

Author: Ellis Amdur Page 5 of 12

Deep in the Caucasus mountains of the Republic of Georgia, there was a place where people still wore mail armour and fought with swords and bucklers well into the 20th Century. This wasn’t a theme park or living history experience, but the region of Khevsureti. Occasionally referred to as The Land of the Lost Crusaders, (a label coined in the 19th century by Russian author Arnold Zisserman, and which scholars from the region have vociferously denied) Khevsureti is a remote region where travel is difficult. Villages that can be seen from one another may have been three days’ walk apart, down a ravine face, across a ford, and up the other side. Perhaps this isolation explains how the Khevsur people managed to preserve their traditional forms of fighting for so long.

BaduanJin 八段錦 (‘eight brocade exercise’) is a classic system of Chinese physical culture. Such systems are generically called qigong. There are an almost innumerable number of qigong sets that integrate, in different proportions, breathwork, stretching, physical exercise and meditative practices. Some are crafted to enhance health; others are for the purpose of developing power or martial arts abilities. Each set can have quite different effects on body and mind. Baduanjin is known to enhance skeletal-muscular fitness and vascular health, as well as enabling practitioners to modulate and control their emotions. The term ‘brocade’ can be interpreted in a variety of ways. One that the author finds most useful is that brocade refers to the body’s web of connective tissue (fascia, ligaments and tendons). These are stretched and strengthened through the integration of specific physical movements with certain breathing techniques.

I have moved this piece, excerpt above, to my Substack, where much of my shorter work, particularly that not directly concerned with martial arts, will be published.

Purchase Books By Ellis Amdur Here

NOTE: IF ANY OF MY READERS HERE FIND THEMSELVES GRATEFUL FOR ACCESS TO THE INFORMATION IN MY ESSAYS, YOU CAN EXPRESS YOUR THANKS IN A WAY THAT WOULD BE HELPFUL TO ME IN TURN. IF YOU HAVE EVER PURCHASED ANY OF MY BOOKS, PLEASE WRITE A REVIEW – THE OPTION IS THERE ON AMAZON AS WELL AS KOBO OR IBOOK. TO BE SURE, POSITIVE REVIEWS ARE VALUABLE IN THEIR OWN RIGHT, BUT BEYOND THAT, THE NUMBER OF REVIEWS BUMPS THE ALGORITHM WITHIN THE ONLINE RETAILER, SO THAT THE BOOK IN QUESTION APPEARS TO MORE CUSTOMERS.

What Are Kata?

It is in vogue—and has been as long as I can remember—to deride kata as idealized, sterile, impractical choreography, a poor simulacrum of real combat. Only through unrestricted freestyle practice, such critics say, can one truly understand the realities of combat. Before I question this absolutist assertion, I will start by saying that I’m a proponent of sparring, and freestyle practice—but it is not fighting any more than pattern drills are. Only fighting is fighting. Once you bring weaponry in, how do you do this safely without killing each other? In fact, that is true for unarmed competition as well.

Araki Murashige (荒木村重)

Araki Murashige was a warlord in central Japan, from an area that encompassed Settsu, Itami, and Izumi (all part of current-day Osaka prefecture). For a relatively brief period of time, Murashige sided with Oda Nobunaga when the latter’s sphere of influence started extending into his region. Murashige was a man of culture and leadership, exemplifying two values Nobunaga treasured. He became one of his top generals, alongside such legendary warriors as Toyotomi Hideyoshi, Shibata Katsuie, and Akechi Mitsuhide.

Nobunaga was a paradox—an elegant beast. His character was perhaps similar to one of Machiavelli’s princes: intellectually curious and highly adaptable, yet utterly ferocious when opposed, a man responsible for the torture and slaughter of tens of thousands of men, women, and children.

In a recent blog, I questioned the mythos around the founders of various traditional ryūha. However, beyond the question of whether the founder truly created his martial system in the archetypal manner that is the usual account, there are several other questions:

- Did the putative founder actually have any role, direct or indirect in the creation of a particular fighting system?

- Did the founder even exist?

A very common trope in the accounts of the origins of traditional Japanese martial arts goes as follows:

According to the Takenouchi Keisho Kogo Den . . . Takenouchi Hisamori retired to the mountains near the Sannomiya shrine to train his martial skills. He practiced there for six days and six nights, wielding a bokken (wooden sword) two shaku and four sun in length (about 2 ft. 4 in. or 72 cm), a relatively long weapon for his purportedly short stature. On the sixth night he fell asleep from exhaustion, using his bokken as a pillow. He was awakened by a mountain priest with white hair and a long beard who seemed so fearsome to Hisamori that he thought it must be an incarnation of the avatar Atago Gongen. Hisamori attacked the stranger, but was defeated. The priest said to him “When you meet the enemy, in that instant, life and death are decided. That is what is called hyōhō (military strategy).” He then took Hisamori’s bokken, told him that long weapons were not useful in combat, and broke it into two daggers one shaku and two sun long. The priest told Hisamori to put these in his belt and call them kogusoku, and taught him how to use them in grappling and close combat. These techniques became called koshi no mawari, (around the hips). The priest then taught Hisamori how to bind and restrain enemies with rope, using a vine from a tree. Then the priest disappeared mysteriously amidst wind and lightning. – Wikipedia entry Takenouchi-ryū (with several grammatical corrections by this author)

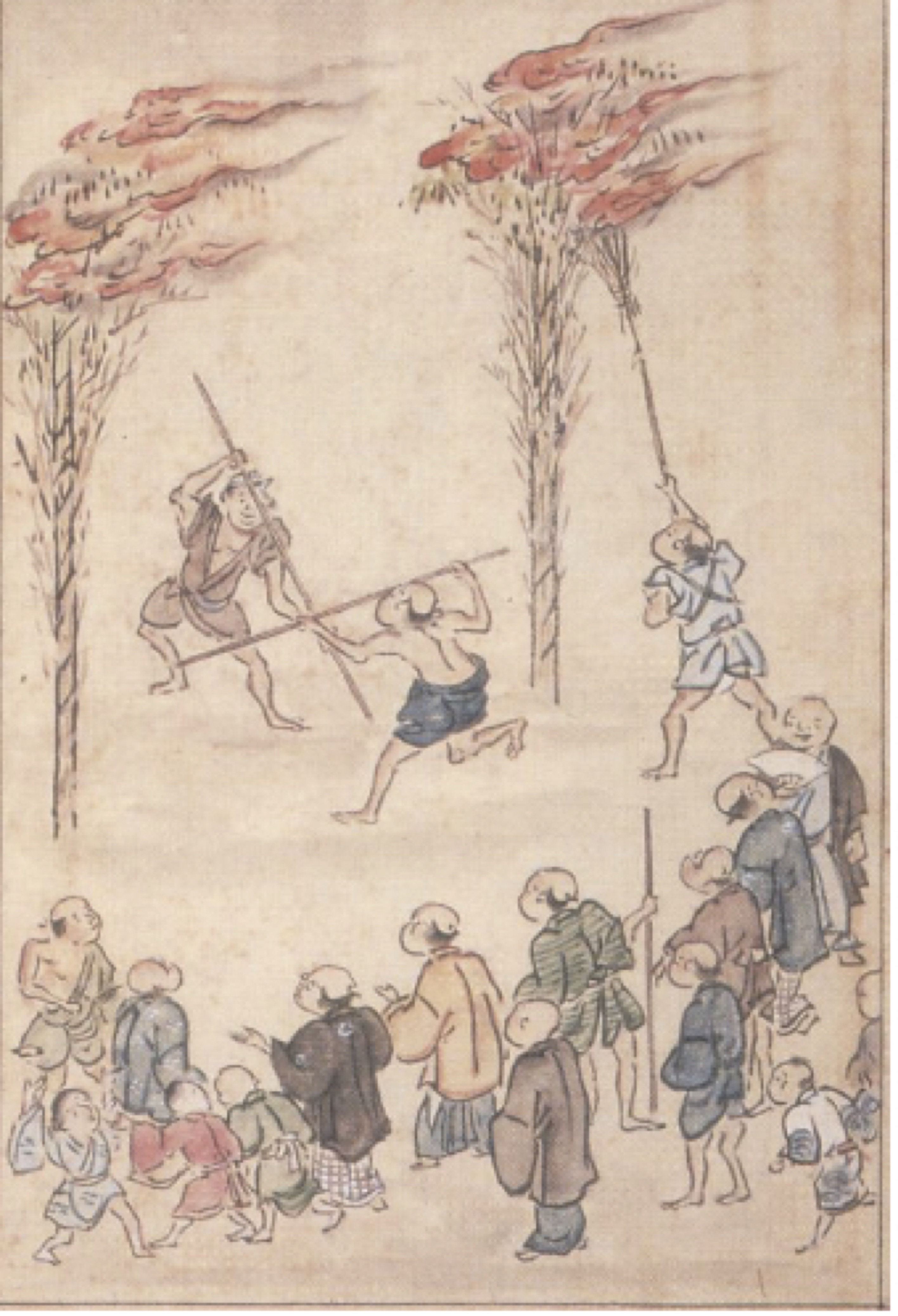

Bōnote (‘staff and hand’) is a festival-centered activity focused around small groups in the old Mikawa and Ryūsenji districts of Aichi. Collectively they hold numerous presentations at many local shrines and events in the surrounding areas, and have even flown overseas to demonstrate. For over 300 years, participants of bōnote have gathered at shrines to practice, organize and perform techniques with weapons as an offering to the ‘spirits of the altar,’ as well as parading new horses, and making offerings to ensure blessings and good fortune.

Bōnote was originally made up of groups called ryū or ryūha whose primary function was to teach prearranged training drills called kata to their members. The area where one lived decided which ryū each person belonged to, and the length of time spent performing, determined the ‘rank’ each person had, and what position they held in the group’s organization.

Bōnote was originally made up of groups called ryū or ryūha whose primary function was to teach prearranged training drills called kata to their members. The area where one lived decided which ryū each person belonged to, and the length of time spent performing, determined the ‘rank’ each person had, and what position they held in the group’s organization.

The kata of bōnote could be summed up as positioning, striking, and evading within set patterns. Going further, what is taught within those patterns is the number and frequency of striking; deflections, blocks and evasions; hand, leg, and body positions: all of which is accompanied by kakegoi (‘spirit yelling’).

A typical bōnote arsenal consists of bō (wooden sticks), yari (spears), uchigatana (disposable ‘side swords’), nagagama (war hooks), kama (sickles), naginata (glaives), and a host of others. Sticks are the primary training tool and a legitimate all-purpose substitute for the other weapons; they are what beginners start training with because authentic weapons are expensive and not something one wants to damage in training. Of course, they are also much safer.