Bōnote (‘staff and hand’) is a festival-centered activity focused around small groups in the old Mikawa and Ryūsenji districts of Aichi. Collectively they hold numerous presentations at many local shrines and events in the surrounding areas, and have even flown overseas to demonstrate. For over 300 years, participants of bōnote have gathered at shrines to practice, organize and perform techniques with weapons as an offering to the ‘spirits of the altar,’ as well as parading new horses, and making offerings to ensure blessings and good fortune.

Bōnote was originally made up of groups called ryū or ryūha whose primary function was to teach prearranged training drills called kata to their members. The area where one lived decided which ryū each person belonged to, and the length of time spent performing, determined the ‘rank’ each person had, and what position they held in the group’s organization.

Bōnote was originally made up of groups called ryū or ryūha whose primary function was to teach prearranged training drills called kata to their members. The area where one lived decided which ryū each person belonged to, and the length of time spent performing, determined the ‘rank’ each person had, and what position they held in the group’s organization.

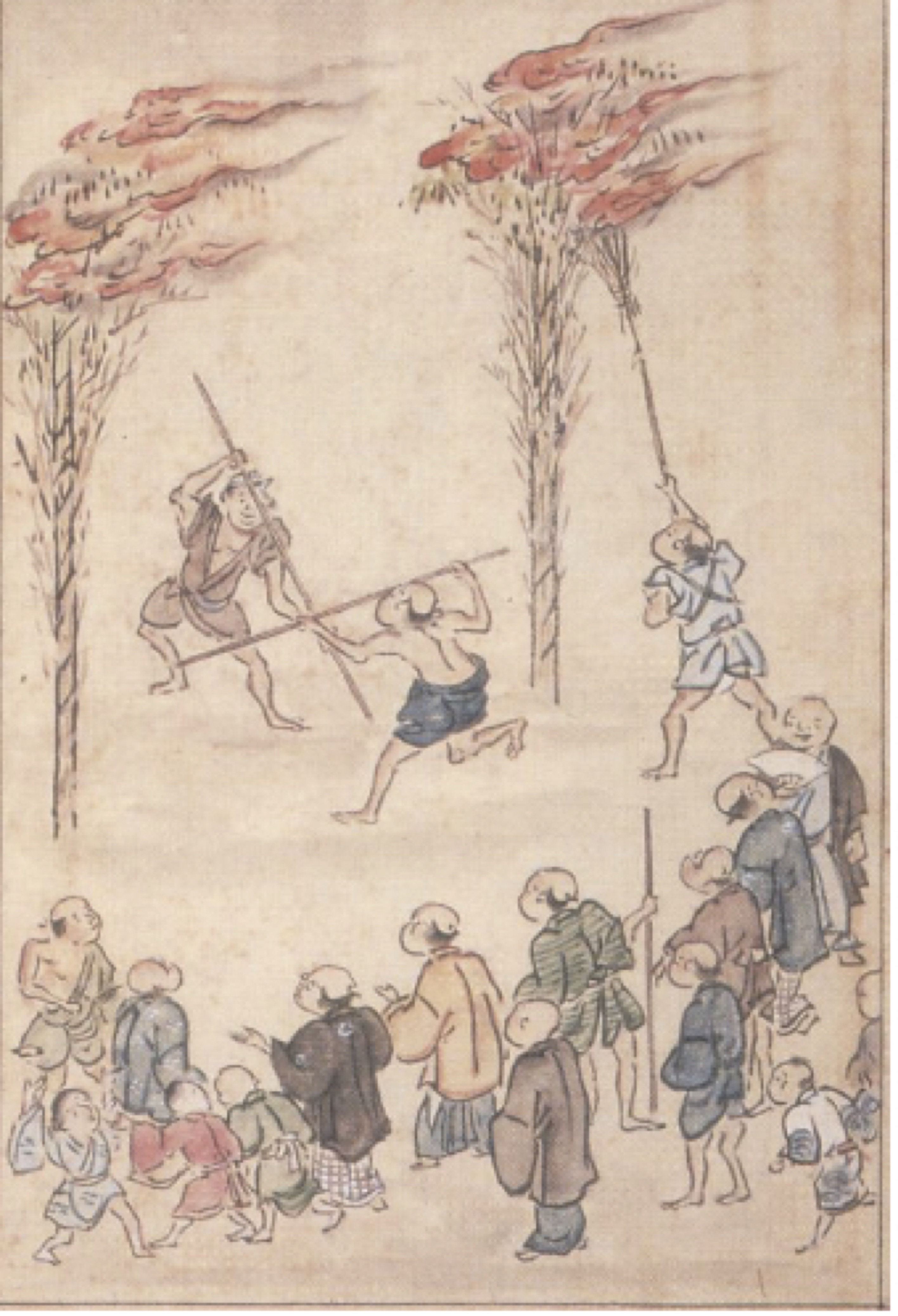

The kata of bōnote could be summed up as positioning, striking, and evading within set patterns. Going further, what is taught within those patterns is the number and frequency of striking; deflections, blocks and evasions; hand, leg, and body positions: all of which is accompanied by kakegoi (‘spirit yelling’).

A typical bōnote arsenal consists of bō (wooden sticks), yari (spears), uchigatana (disposable ‘side swords’), nagagama (war hooks), kama (sickles), naginata (glaives), and a host of others. Sticks are the primary training tool and a legitimate all-purpose substitute for the other weapons; they are what beginners start training with because authentic weapons are expensive and not something one wants to damage in training. Of course, they are also much safer.