Araki Murashige (荒木村重)

Araki Murashige was a warlord in central Japan, from an area that encompassed Settsu, Itami, and Izumi (all part of current-day Osaka prefecture). For a relatively brief period of time, Murashige sided with Oda Nobunaga when the latter’s sphere of influence started extending into his region. Murashige was a man of culture and leadership, exemplifying two values Nobunaga treasured. He became one of his top generals, alongside such legendary warriors as Toyotomi Hideyoshi, Shibata Katsuie, and Akechi Mitsuhide.

Nobunaga was a paradox—an elegant beast. His character was perhaps similar to one of Machiavelli’s princes: intellectually curious and highly adaptable, yet utterly ferocious when opposed, a man responsible for the torture and slaughter of tens of thousands of men, women, and children.

Araki Murashige was born in 1535, the son of Araki Shinano no Kami Yoshimura, one of the six leading retainers of Ikeda Katsumasa. As a child, Murashige was one of Katsumasa’s pages. In 1563, when Katsumasa succeeded his father as feudal lord, other family members, led by Ikeda Kagaemon, revolted against him. Murashige led a group that assassinated Kagaemon and eight of his followers while they were holding a drinking party.

In 1568, Nobunaga went to Kyoto, ostensibly to help the beleaguered shogun, Ashikaga Yoshiaki. In the process, he displaced two of his enemies, the Miyoshi and Hatakeyama clans. Nobunaga chased the Miyoshi into their holdings in nearby Settsu, and while there, he surrounded the Ikeda castle. Katsumasa surrendered and pledged loyalty to Nobunaga. However, because he did not do so ‘soon enough,’ Ikeda was never in Nobunaga’s favor.

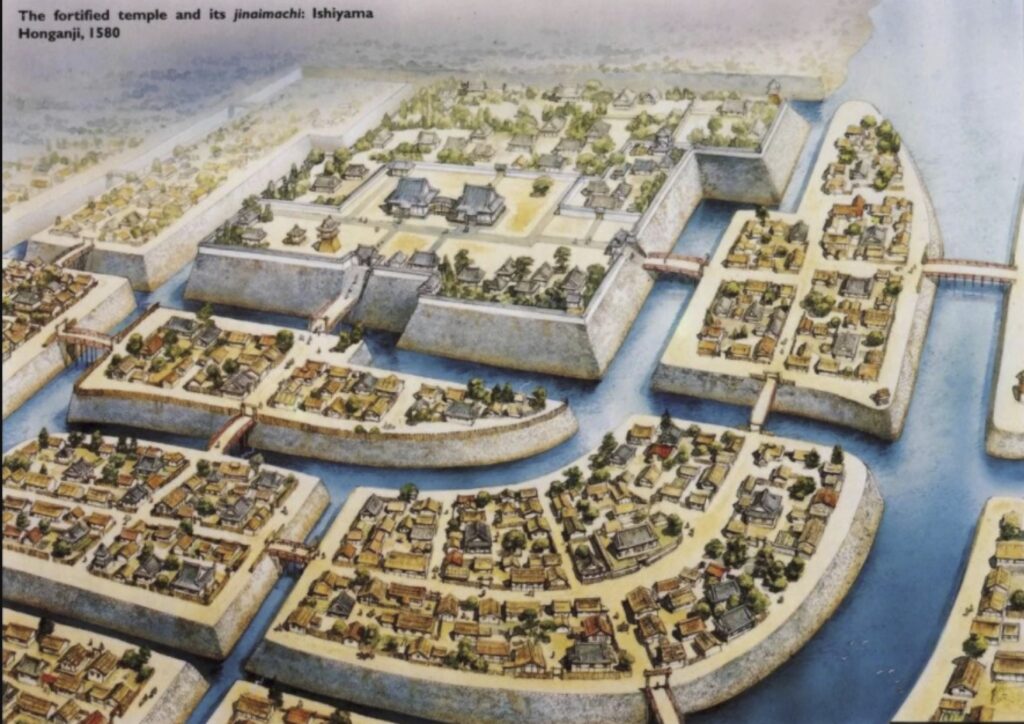

During this campaign, Nobunaga also began his gradual assault on the huge Ishiyama Honganji, a temple complex of the Ikkō-shū, also in Settsu. It was a huge complex, almost a city-state, at the mouth of the Yodo River, along the Seto Naikai (‘Seto Inland Sea’). Ikkō-shū was a sect of Buddhism that fostered an ostensibly egalitarian opposition to the feudal system of lords and retainers, although, in truth, the Ikkō-shū functioned as another kind of hierarchical organization, led by priests rather than feudal lords. Of them, the Jesuit Padre Gaspar Vilela wrote that they:

kept no rule, did not fast, and were more mercenary soldiers than anything else. He noted that they each made seven arrows daily, held weekly musketry and archery competitions, and spent all their time in practicing rigorous military exercises. He observed that their weapons were correspondingly efficient, for their great swords could cut through a man in armor ‘ as easily as a sharp knife cleaves a very tender rump,’ . . . . They believed (so he says) in a short life if a gay one, for they readily hired themselves out as mercenaries to warring daimyo, and atoned for the resultant heavy casualty rate by eating, drinking, and making merry generally . . . (1)

Due, however, to their religious doctrine, which promised a better life, not only in a ‘Pure Land’ earned after death through devotion to the Amida Buddha, but in this life as well, the Ikkō-shū inspired fanatical loyalty, particularly among the downtrodden peasantry. Nobunaga’s initial gambit was to levy huge ‘taxes’ against them, attempting, thereby, to pressure them from the ground up. This was a start of a long and ferocious campaign.

At the end of this brief campaign, Nobunaga went back to his home in Gifu. The Miyoshi moved right back to Kyoto, and in 1569, their retainers set fires throughout the city. The majority of the minor lords of Settsu rebelled against the Miyoshi, making common cause with Nobunaga, who return to attack them again. Despite allying themselves with the Ishiyama Honganji, the Miyoshi were defeated. As a political maneuver, Nobunaga appointed Ikeda Katsumasa to be shugo (constable) of his holdings in the area, even though Ikeda did not participate in the fighting, simply withdrawing to wait it out in his own castle.

A year later, Araki Murashige revolted and threw Katsumasa out of one of his own castles. Given that he had previously rescued him, one can only wonder if this was due to some sort of personal affront, or if Murashige was simply reaching for more power. Murashige, unlike most of the warlords in the area, continued to maintain an alliance with the Miyoshi, yet paradoxically, despite this alliance and this attack, he was still considered one of Katsumasa’s retainers.

An Alliance between Murashige and Takayama Ukon: The Christian

Among those other warlords was Takayama Ukon. He is a curious figure—to some a paragon of virtue, to others a traitor. His father, Takayama Tomoteru, was a retainer of Matsunaga Hisahide. Both father and son were devout Christians, a religion that had made astonishing inroads into Japan since the arrival of the Portuguese in the mid 1500’s.

Some years before the incidents in Settsu, Matsunaga murdered the previous shogun, Ashikaga Yoshiteru, and then became embroiled in a war with the Miyoshi. During this conflict, the Takayama castle in Sawa was taken, and they fled to the domain of a friend, Wada Koremasa, lord of Omi, a domain close to Settsu. They took up service with Wada in 1568, and were granted one of his castles. They thereby came under the aegis of Nobunaga.

Settsu, Murashige’s home, was a rich manufacturing area, and it held a strategic position in regards to the Ishiyama Honganji. One of Nobunaga’s spies, Hosokawa Hyogu, a retainer of the shogun, suggested that an alliance with Murashige would be to Nobunaga’s advantage. An agreement was reached, Nobunaga saying to Murashige, “Kiri tori jiyu” (“cut and take as you please”). In essence, Nobunaga indicated that whatever happened between Murashige, the Ikeda, the Wada and any other of the minor lords of the area, was not his concern, even though the latter were, ostensibly, his vassals.

In 1571, the Wada went to war against Araki Murashige. Murashige besieged Takayama’s new castle. Wada Koremasa attacked him with a relief force and was killed. Murashige, nonetheless, was unable to take the castle and retreated.

Koremasa was succeeded by his son, Wada Korenaga. For unknown reasons, relations between Korenaga and Takayama Tomoteru deteriorated, and hearing a rumor that Korenaga was planning to have him killed, Takayama invited him to his home. Korenaga arrived with an armed escort, but Takayama, father and son, along with fifteen retainers, attacked. Korenaga’s group was defeated, yet Korenaga himself somehow managed to escape.

To prepare for this ambush, which could be viewed as either an assassination or a desperate move for survival, Tomoteru previously contacted Araki Murashige and they agreed to jointly take over the Wada domain. Nobunaga made neither move nor comment against any of the parties. The Takayama and Murashige were now allies, and Tomoteru gave his son, Ukon, the leadership role in their new domain.

Araki Murashige in Ascendency

Araki Murashige was still, officially, the vassal of the Ikeda clan, but after they killed his father-in-law, he destroyed their power. In a series of lightning campaigns, Murashige took over all of Settsu and Itami. With the exception of Ishiyama Honganji, he ruled the entire area, formally becoming a vassal of Nobunaga.

While Murashige was consolidating his power, the alliance between Nobunaga and the shogun, Ashikaga Yoshiaki, was irreparably destroyed, and Nobunaga openly moved to take over the entire Japanese archipelago. Murashige’s first successful campaign on Nobunaga’s behalf was to take the castle where the shogun was residing. For the next six years, Murashige was one of Nobunaga’s favorite generals, fighting in at least one battle a year and taking the lead in the siege against the Ikkō-shū at Ishiyama Honganji.

Araki’s Revolt Against Nobunaga

Then in 1578, while Murashige was participating in a difficult campaign in the westernmost area of Honshū, the main island, rumors spread that one of his vassals was breaking the siege at Ishiyama by supplying food and weapons. Furthermore, according to a letter sent by Nobunaga’s spy, Hosokawa Hyogu, Murashige was alleged to be conspiring against Nobunaga himself. Hearing of this, Murashige returned to Settsu and sent a letter to both Honganji and Nobunaga’s most powerful enemies, the Mori, urging them to attack Nobunaga.

Why the rumors started and why Murashige revolted is somewhat of a mystery. Black-market dealings with enemies were quite common at that time. In this case, however, Murashige’s retainer may have been acting directly on his orders. Murashige may have been moved by the fact that most of the members of the Ikkō-shū besieged at Honganji were peasants of Settsu, Araki’s own people. He had gone to Honganji on a diplomatic mission nine months previously, and may have seen the conditions inside. His own country was divided, and his people were starving.

Nobunaga’s initial response was reported to be stunned disbelief. He sent a high-level mission of generals to attempt reconciliation, among them the famous general, Akechi Mitsuhide, whose daughter was married to one of Murashige’s sons. But diplomacy failed. Murashige may have felt entrapped by the rumors, and believing that Nobunaga would mistrust him from that point on, may have decided that he might as well fight to survive rather than wait for the axe to fall. Nobunaga was nothing if not paranoid— whether justified or not, if he decided Murashige was a danger, his days were numbered. Considering his history of opportunism and sudden attacks, however, Murashige may have simply decided to change sides again.

Murashige did not pose an insignificant threat. His actions threatened to break the siege at Honganji. In addition, he offered an inspiration to others who might chafe under Nobunaga’s rule for either moral reasons or a simple hunger for power. Finally, Settsu and Itami, Murashige’s domains, were positioned such that if he were successful, he would be in a position to threaten Kyoto itself.

Takayama’s Betrayal of Araki

Essential to Murashige’s defenses were several castles, one held by his allies, the Takayama—father and son. Nobunaga sent a Jesuit Padre, Gnecchi-Soldo Organtino, to the Takayama. Simultaneously ambassador and cats-paw, Organtino suggested that surrender to Nobunaga would be of benefit to the Catholic Church, but if they did not surrender, Nobunaga had hinted that the consequences would be unfortunate for all Christians in Japan. Of course, ‘unfortunate’ in Nobunaga’s terms was horrifying to contemplate. Takayama Ukon, devoutly Christian, abandoned the castle in the middle of the night, shaved his head to signal his resignation from the warrior class and presented himself to Nobunaga, taking full responsibility upon himself.

Although a Christian as well, Ukon’s father was outraged, and he went to Murashige to apologize, both for the blot upon the family honor, and also in hopes of saving a number of hostages that Murashige held, in the conventions of the day, to ensure the Takayamas’ loyalty. Murashige, no murderer, released the Takayama hostages. However, those left in command of Takayama Ukon’s fortress did not see themselves bound by ties of loyalty to Murashige, and they surrendered to Nobunaga. Nobunaga rewarded Ukon, who had expected death, with the return and even the expansion of his holdings. Without Takayama’s forces, Araki posed no threat to Kyoto. (2)

A Tiger without Fangs

Murashige, now isolated, held out for almost a year. In the autumn of 1579, he fled his castle and went to that of his son, Araki Shingoro, abandoning six hundred men, women, and children, including most of his own family. Nobunaga, to make a savage example to any future rebels, had all six hundred killed—by blade, bullet, and crucifixion. Murashige’s family members were beheaded or burned to death.

Among the small party that escaped with Murashige was a wet nurse carrying his baby son, Araki Katsumochi. They were eventually given refuge in a branch of the Hongan Temple in Kyoto.

A year later, Araki Shingoro’s castle was also taken. Murashige escaped by sea and hid out with the Mori clan, resurfacing when Nobunaga was assassinated by his own general, Akechi Mitsuhide. Murashige’s star, however, was burned out. A leading disciple of the tea master, Sen no Rikkyu, he became a lay-monk. His name was ‘Dōkun,’ which means, ‘Scent of the Tao.’

He became an otogishū to Toyotomi Hideyoshi, who had destroyed Akechi in a lightening campaign, and was, at that time, well on his way to taking over all of Japan. The otogishū were a group of former high-ranking aristocrats and warlords who had fallen from glory. Hideyoshi, the consummate political animal, kept these men close to him so that they would have no opportunity to again gather power. Also sentimental (Hideyoshi’s letters are a remarkable study in character—a man who could order genocide in Korea, and yet be anxious about his relations with his children), he kept these men, with a combination of condescension and pity, like pets: tigers without fangs who could no longer survive in the wild. There is a record of Hideyoshi buying Murashige’s tsubo (a container used to boil water for tea) at a very high price, perhaps to help Murashige support himself.

According to Luis Flores, a contemporary Portuguese historian, Murashige encountered Takayama Ukon, another of Sen no Rikkyu’s disciples, at a gathering of Hideyoshi’s. Face-to-face with the man whose betrayal ensured the failure of his revolt and the slaughter of his family, Flores writes that Murashige merely complained, “His insides and outsides are different.” However, even so mild a criticism of Ukon was taken as an implicit censure of Hideyoshi, and Murashige fell from favor. After 1586, his name no longer appears on any tea ceremony lists, and his name appears on a gravestone marker bearing that date in Itami.

Murashige’s Descendents

Murashige did have a few surviving descendents. Araki Katsumochi, his infant son, later became a famous painter, using his mother’s maiden name, Iwasa Matabei. His paintings are known to have displayed a remarkable psychological depth. He is considered one of the founders of the ukiyoe (floating world) style of art, which portrays the evanescent nightlife of the licensed quarter. He became very prominent, working for a number of daimyo, including Oda Nobuo, Nobunaga’s grandson. He died in 1650.

A cousin, Araki Shima no Kami, was an ally of Hideyoshi, and he is known as the founder of Araki-ryū bajutsu, a school of horsemanship that reportedly survives to this day.

One daughter, Araki Tsubone was, from childhood, a hostage at Honganji Temple. There, she was educated in ritual and etiquette. (Tsubone lit. ‘The women’s court,’ is a name that denotes her condition in life rather than a given name). After the Ikkō-shū surrendered, she became a powerful figure in Tokugawa’s ‘harem’ of concubines—officially a mistress, but actually one of the older women who enforced the rules. In fact, the word otsubonesama, taken from her name, means a ‘controlling, manipulative, nasty old woman.’

Araki Shingoro, Murashige’s most prominent son, was killed in the war with Nobunaga, leaving a three-year-old son, Araki Muratsune. Muratsune was brought up by an uncle, and later figured in the first battle for Osaka castle—once again, an Araki was on the wrong side as he allied himself with Toyotomi Hideyori. He escaped however, and, in 1638, he gained prominence in opposition to the Shimabara rebellion, fighting on the side of those suppressing the Christians. He thereby gained favor with the third Tokugawa shogun and, apparently with the help of his aunt, Araki Tsubone, did well for some years. When she was demoted in a scandal, he lost favor as well, and as far as history is concerned, this was the end of the Araki as a warrior family.

That some lines of Araki-ryū claim a connection to Araki Murashige is understandable—this is a great story. Murashige was one of those ‘Noble Failures’ so beloved in Japanese legend—despite betrayal, he didn’t kill his hostages, and he revolted against a juggernaut, stopping it in its tracks for one year. So what does this story illuminate? Imagine this era, the ‘Warring States Period,’ like a multilayered chessboard on which the pieces suddenly change color or even bear two shades at once. The rule was betrayal, and military tactics included slaughter and terrorism.

Footnotes

(1) Boxer, C.R., The Christina Century in Japn: 1549 – 1650 University of California Press, Berkeley, California, p. 68

(2) Tomoteru later renounced Christianity and died in 1595. Takayama Ukon continued a colorful career in the service of Nobunaga, Hideyoshi, and Tokugawa Ieyasu. Among other things, he was known for his forced conversions of thousands of Buddhists to Christianity, a matter of indifference to his warlords as long as they were engaged in shattering the secular power of the Buddhist temples. Once this was accomplished, however, Christianity was regarded as a potentially revolutionary force and also as the means by which the Europeans would gain power in the country. Therefore, in 1615, Ukon and his family were exiled to the Philippines. He took up residence with local Jesuits and died six months later. He has been proposed for sainthood by the Catholic church.

No part of this material may be reproduced in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, without permission in writing from the author. However, you are welcome to share a link to this article on such social media as Facebook, LinkedIn or Twitter.

Purchase Books By Ellis Amdur Here

NOTE: IF ANY OF MY READERS HERE FIND THEMSELVES GRATEFUL FOR ACCESS TO THE INFORMATION IN MY ESSAYS, YOU CAN EXPRESS YOUR THANKS IN A WAY THAT WOULD BE HELPFUL TO ME IN TURN. IF YOU HAVE EVER PURCHASED ANY OF MY BOOKS, PLEASE WRITE A REVIEW – THE OPTION IS THERE ON AMAZON AS WELL AS KOBO OR IBOOK. TO BE SURE, POSITIVE REVIEWS ARE VALUABLE IN THEIR OWN RIGHT, BUT BEYOND THAT, THE NUMBER OF REVIEWS BUMPS THE ALGORITHM WITHIN THE ONLINE RETAILER, SO THAT THE BOOK IN QUESTION APPEARS TO MORE CUSTOMERS.

Chris Leblanc

A most fascinating time in history. Nobunaga and Hideyoshi remain subjects of deep fascination. Whether Araki-Ryu has any connection or not to Murashige, it most certainly does to this time. What seems to be missed in so much martial arts research and writing and origin stories is historical reality: the ryu and ryuha that developed even a little bit later – mid 1600s or so, were created in a society and martial milieu that was world’s apart from this one.