In 1985, at Waseda University, Ellis Amdur gave a Japan Martial Arts Society presentation on “Self-Defense in Japan.” There, he quoted a Buddhist precept, “Do no unnecessary harm.” This phrase, which I have never forgotten, was reinforced by what I was told by my Tatsumi-ryū seniors. It has become part of my personal ethos ever since. For example when they explained the duties of a kaishaku, I was told that he should act at his own discretion, and not wait for the person committing seppuku to stab himself in the stomach. Rather, the kaishaku should cut the person’s neck immediately when he leans forward to pick up the dagger or short sword which will have been placed before him. Placing the blade at an appropriate distance from the person to be executed will ensure that his neck is at the optimum distance and angle for the kaishaku to cut.

It was conveyed to me that Tatsumi-ryū is not morally neutral. You are not permitted to take part in sadistic practices, much less enjoy what you are doing, as it clouds your mind and works against you being in mushin (“flow state”). To sum up the Tatsumi-ryū approach, if you have to kill somebody to stop them for whatever reason, you may do so, but you should act like the professional you are, and use only as much violence as is absolutely necessary. From 22:30 until 23:00 within the Korean language “Asian Masters” documentary, Kato Hiroshi sensei, the 22nd headmaster of Tatsumi-ryū explains the essence of seven admonitions that are necessary to achieve this flow state.

SEVEN ADMONITIONS

| ON yomi | KUN yomi | Kanji | Admonition |

| Kyo | odoroku | 驚く | Do not allow yourself to be surprised, surprise the enemy |

| Ku | osoreru | 恐る | Do not give into fear, make the enemy afraid |

| Gi | utagau | 疑う | Do not doubt yourself, make the enemy doubt himself |

| Waku | madou | 惑う | Do not be led astray or deceived, lead the enemy astray |

| Kan | yurumeru | 緩める | Do not lose concentration, make the enemy lose concentration |

| Mu | ikaru | 怒る | Do not become angry, make the enemy angry |

| Sho | aseru | 焦る | Do not be hasty, make the enemy act in haste |

RESPECT

The flow state alone, however, can conceivably be amoral. Therefore, the starting point for the ethical warrior is respect. The Japanese saying is “Rei de (or ‘ni’) hajimari, rei de (or ‘ni’) owaru.” (“Budo begins and ends with a bow.”) The original Japanese is 礼に始まり礼に終わる. (NB: if the other particle is used, 礼で。。。) I think, however, that translating rei merely as “bow” minimizes its importance. I would prefer to translate it as “respect” in the broadest sense. Respect for yourself, respect for the other, and yes, even respect for your enemies. They are human, and if they are to be killed, they should be killed as respectfully as possible.

I would venture that it is easier to create an atmosphere of respect in small groups. Typically, ryu are small bodies of compatible people under strong leadership who share a common world view. I have a fond memory which may serve as an example of such cohesion. After training, we (the Tatsumi-ryū seniors) would go through “house-keeping:” recent and forthcoming promotions, upcoming gasshuku and demonstrations, the exegesis of historical documents, etc. On a chilly winter’s night, we would make sure that there was a heater to keep Kato Takashi sensei warm. The only problem was that he would keep fiddling with the heater, turning it away from himself so that we would get warm. That’s just one small example of how he cared for his students. As an example of disrespect, I remember him telling me about an incident that he witnessed during WWII. A Japanese officer hit an enlisted man across the face (temple area perhaps) with his sheathed military sabre. The enlisted man later died of the injury. Kato Sensei was very disapproving, saying it was a despicable abuse of authority, and disrespectful in the extreme to the victim.

It is a commonplace that no-one has clean hands, and that history is written by the victors. This is not to say that all parties to a conflict are morally equivalent. Nonetheless, every country seems to have disgraced itself on occasion, exhibiting extreme savagery. One thinks of Turkey’s massacre of the Armenians and the Fall of Constantinople in 1453; the savage reprisals of the Nazis against the resistance in occupied Europe, and beyond that, the Nazi’s “Final Solution;” the Rape of Nanking by the Japanese, and so on. If you’re an American, there’s the deliberate starting of firestorms to attack the civilian population of Tokyo and other Japanese cities, not to mention the atomic bombs dropped on Hiroshima and Nagasaki. If you’re a British citizen/English speaker, don’t consider yourself and your compatriots blameless: there’s the carpet bombing of Dresden, and if we go back a little further into the past, there’s the first use of concentration camps by the British in South Africa during the Second Anglo-Boer War, 1899 – 1902, to force the Afrikaners to stop their guerrilla campaign against the British Empire, as well as the horrendous Sack of Badajoz in 1812 by British troops under Wellington during the Napoleonic Wars. It took three days to bring the soldiers back under control, and several British officers were killed when they tried to re-impose discipline during the massacre.

Victor Davis Hanson, one of the foremost American military historians, points out Nazi Germany’s obsessive persecution of the Jews, continuing to spend personnel and resources on the so-called “Final Solution,” even when it was clear that the Nazis were losing. Similarly, should you be so focused on gang-raping your enemy’s women, torturing the elderly and beheading children that you leave your enemy no choice but devastating counter-attack, I would suggest that you may have lost track of reality. Such loss of clarity, when one is intent only on rape and carnage, may come about though the very nature of one’s society itself, through the mediums of cultural indoctrination, and/or indulgence in some form of drugs or alcohol, possession, sadistic cruelty, torture, and/or sexual violence.

Starting with The Western Way of War, Victor Davis Hanson develops his theme that some uniquely Western institutions make the West a formidable opponent in war. Being a citizen and not a subject, having freedom of speech, a tradition of dissent, and prizing inventiveness and adaptation, consistently produces superior armies, weapons, and soldiers. The social anthropologist Mary Douglas pointed out that the Social Body constrains how the Physical body is perceived. Briefly, cultures are not cobbled together at random; they are internally consistent. Thus flaws in the strategy and tactics of the “Savage” will reflect the flaws in their societies.

My table below attempts to contrast the Ethical Warrior with the Savage.

| THE ETHICAL WARRIOR | THE SAVAGE |

| Respects his opponent’s humanity | Disrespects |

| Seeks clarity/the real | Avoids/Distorts reality |

| Self-examination | Avoids self-examination |

| Disciplined | Undisciplined |

| Flow State | Emotionally aroused |

| Distinguishes between combatants and non-combatants | Does not distinguish |

| Merciful whenever possible | Merciless |

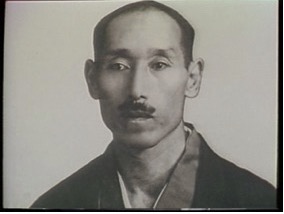

Kato Hisashi: An Ethical Warrior

One Saturday afternoon, when I’d only been doing Tatsumi-ryū for about a year or so ( at this stage there weren’t many students, and I was getting private lessons from Kato Takashi sensei, squeezed in before a children’s kendō class ), Kato sensei said to me that we wouldn’t be training that day, that, instead, he wanted me to visit his father’s grave with him. There was a large memorial stone giving some details of his father’s life, which he explained to me. His father had been mentored by the leading figures in early kendō history, such as Takano Sasaburo, Nakayama Hakudo, and Mochida Seiji. Kato Hisashi was the 19th Headmaster of Tatsumi-ryū. He was known as “Yatomi no Seijin” (the Saint of Yatomi, a district in Sakura City in what is now Chiba Prefecure) to the locals because of his exemplary moral character. I always think that Kato Hisashi sensei looks like he could be a philosopher or a poet, but he must have been an outstanding swordsman, because he was one of a few very high-ranking martial artists selected to demonstrate traditional Japanese martial arts to a Hitler Youth delegation just prior to WWII. He demonstrated iai and tameshigiri. A lot of what Kato sensei told me didn’t mean much to me at that time, since I didn’t know much about kendō history. One of the incidents that was recorded on the memorial is one which I have always remembered was Kato Hisashi sensei’s saving six Koreans from a lynch mob after the great Kantō earthquake of September 1st, 1923. Shamefully, rabble rousers blamed the earthquake on the Korean minority and there were massacres of Koreans in several localities. It is said that over half the Koreans living in Yokohama were massacred. Some elements of the military and the police were involved, and they and vigilantes took advantage of the frenzy to kill political rivals including socialists, communists, and anarchists in addition to the Koreans. The victims were stabbed with bamboo spears or beaten to death with farming tools. Neutral observers estimate over six thousand people were slaughtered in the weeks following the earthquake, though the Japanese government strongly denied it. Kato Hiroshi sensei, currently the 22nd Headmaster of Tatsumi ryu and the grandson of Kato Hisashi, told me several years later, that Hisashi sensei smuggled the Koreans to safety by dressing them up as local volunteer firemen. Recently my students were talking about satsujinken (the “murderous sword) and the katsujinken (the “life-giving sword”). I can think of no better example of katsujinken than Kato Hisashi sensei’s moral courage and humanity on this occasion.

(NB: I originally posted this article on Facebook on the 16th of June 2021. I have made some slight additions.)

Bibliography

- Hanson, Victor Davis, The Western Way of War: Infantry Battle in Classical Greece, Oxford University Press, 1989

- Hanson, Victor Davis, Carnage and Culture: Landmark Battles in the Rise of Western Power, Doubleday, Random House, New York, 2001

- Keeley, Lawrence, War before Civilization: The Myth of the Peaceful Savage, Oxford University Press, New York, 1996

- Schlichter, Kurt, “Accept That Savagery Is The True Nature Of The World And Deal With It”

- Wrangham, Richard, The Goodness Paradox: The Strange Relationship Between Virtue and Violence in Human Evolution, Pantheon, 2019