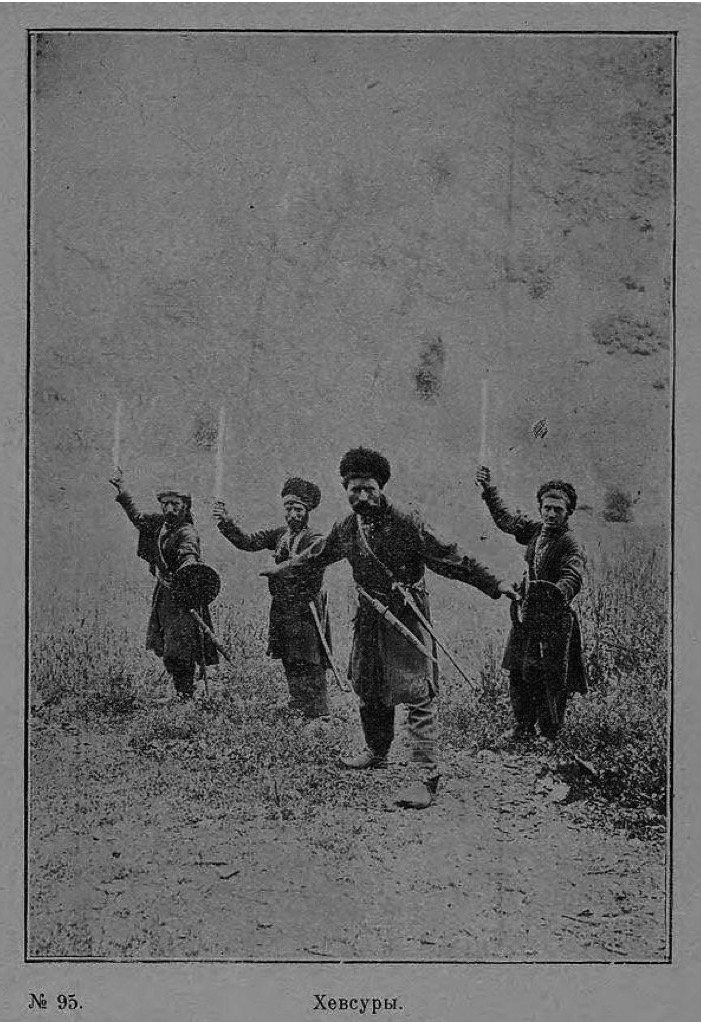

Deep in the Caucasus mountains of the Republic of Georgia, there was a place where people still wore mail armour and fought with swords and bucklers well into the 20th Century. This wasn’t a theme park or living history experience, but the region of Khevsureti. Occasionally referred to as The Land of the Lost Crusaders, (a label coined in the 19th century by Russian author Arnold Zisserman, and which scholars from the region have vociferously denied) Khevsureti is a remote region where travel is difficult. Villages that can be seen from one another may have been three days’ walk apart, down a ravine face, across a ford, and up the other side. Perhaps this isolation explains how the Khevsur people managed to preserve their traditional forms of fighting for so long.

The Georgians who lived in these remote mountain villages were historically renowned as fighters. Their sword-fighting was culturally codified into three distinct levels; from friendly contest to all out war, these were parikaoba, chra-chriloba, and lashkroba. The Khevsur practiced both the friendly parikaoba to demonstrate prowess, and the less friendly chra-chriloba dueling to settle disputes. Khevsurs would attempt to show their skills by simply touching each other with the unsharpened part of the sword (the spine or the flats) in parikaoba, or to inflict bleeding head wounds on their opponent in chra-chriloba. There was an elaborate system of compensation if one wounded an opponent outside of the allowed target area (the head, above three folds of the forehead according to V.I. Elashvili). Wounds that extended into the clear portions of the face were measured in grains and compensation in sheep or cattle was paid to the wounded party. Inaccuracy could thus bankrupt a family, even if they won the duel. Like other tribal customs in the region, if a woman tossed or placed her head covering between the fighters they were required to stop the fight. These fights were so common that one Russian doctor observed that over half the young Khevsur recruits he processed into the military already bore scars in their scalp by age eighteen.

Martial skill and military service were ingrained in Khevsur culture. While most of Georgia served feudal lords who in turn served the monarch, the Khevsur people elected their own village leaders and served the monarch directly. In return for this freedom, they gave succor to the monarch on those frequent occasions when he had to flee the Georgian lowlands, and in times of war, the highlands emptied and the Khevsur all came to fight for him.

Interestingly, to those who may be familiar with the well known Georgian wrestling art of chidaoba, the Khevsur did not focus on unarmed arts. They instead preferred to focus on the use of weapons, particularly blades of various sorts, and a form of fighting ring known as a ghaj’ia or a satseruli, which was worn on the thumb. This focus on weapon use ran deep! For example, a Georgian martial arts instructor–one who had sought out remaining knowledge of these forms from Khevsur elders once asked what he should do if he found himself unarmed. The elder responded, “There are rocks. Pick one up and hit him with it!”

Fully armed, a Khevsur warrior carried at least 3 blades. On his left, slung from a baldric and hanging high into his armpit was his khmali, or broadsword. This was a straight or slightly curved single-edged blade with a cruciform hilt and a downturned pommel, typically around 34” (80-90 cm) long. Hanging from his belt by a single strap, vertically, also on his left was the dashna, or shortsword. Generally single edged, this blade was shorter, typically 20-24 inches (50-60cm), and it usually had a hilt in the same style as a kindjal dagger. Hanging at an angle at the front of his belt was his dagger, called a khanjali or a satevari in Georgian. This was double-edged, and perhaps the most famous weapon design to come out of Georgia. Lastly, angled at the left might be the ursa or belt-knife; still smaller, this was more of a utility knife that could double as a weapon in a pinch. He would also typically carry a flat, round buckler, called a pari, made of metal or hide with multiple layers of metal reinforcement on the face that was gripped by wound leather straps. This could vary in size from barely larger than a fist, up to 20” (50cm) in diameter, but was typically around 11” (28cm). He also carried a bandolier of cartridges that settled into the same place as the cartridge loops seen on the famed chokha jacket which was adopted by the Cossacks.

These weapons were all worn over a mail hauberk, or dzhachvis perangi, which had long sleeves and draped to at least mid- thigh, split at the sides up to the waist for movement. This was sometimes slightly open near the neck, and often would be hooked or tied closed. On his head, he would wear nothing but a sort of steel skullcap with mail hanging from the edges called a napleshnik, or a simple mail coif which might have an open face, open eyes only, or even no openings in the front. Unlike western European armours, while a Khevsur might don the napleshnik over his hat, there was no dedicated padding inside the headgear. Aside from this, the only common armour was a pair of bazubands, called samklaveni in Georgia, (these were virtually identical in form to the Persian ones, enclosing the forearm in three plates connected by metal rings and projecting on the outside up to and slightly past, the elbow) and a pair of mail mittens to protect the hands. Under their armour, the Khevsur would be garbed in their traditional brightly embroidered heavy woolen tunic known as a talevari. This, like the mail, was split up the side to the hip for ease of movement.

By reading the preceding paragraphs you might get the impression that this is, like so many others, a wholly dead art, that the lineage was broken and the knowledge lost completely when Stalin purged Khevsureti and resettled the Khevsur elsewhere in the Soviet Union. Fortunately, while direct lineage from master to student no longer exists, efforts were made beginning in the 1990s to gather the remaining knowledge, preserve it, and pass it down. I joined these efforts in the early 2000s when, as a practitioner of classical and historical Italian fencing under Maestro Sean Hayes, I ran across V.I. Elashvili’s text, Parikaoba, (the best written source on Khevsur swordplay), while looking for Russian sabre manuscripts. After translating enough of the document to realize what I was looking at, I began to seek out the existing Georgian authorities on the subject, obtain appropriate practice equipment, and develop a functional interpretation of the material. Now, over 15 years later, I am still continually revising my perspective as some new interview or story is found that confirms or overturns something that we thought we knew about how this was practiced. The following material about the practice of Khevsur martial arts is my understanding as of February of 2021.

The truly unique thing about Khevsur swordplay is the way the sword (khmali or dashna) and buckler were used together. Since this style was used as late as the 1950s in serious practice, we not only have written and oral records, but photographs and even some bits of old ethnographic film that show (parikaoba), the friendliest of the three distinct modes of fighting in Khevsureti. If you want to get a feeling for the main guard position of Khevsur fencing, you may begin by placing your feet shoulder-width apart and nearly parallel with your shoulders. One foot may be slightly more forward than the other. Grip your buckler by the straps with your knuckles flat to its back, as if you were punching, and hold the sword in a firm hammer grip. Bend your arms and place your sword right behind your buckler, such that your thumbs are touching, and the sword is as close behind the buckler as it can get with the blade pointed straight up (you may overlap the thumbs if you like to help hold the hands together, especially at first). Squat slightly as if you had a barbell on your shoulders and were performing a back squat. Lastly, tuck your elbows in so that they are protected by the buckler as much as possible. This is the first and most important guard position in Khevsur swordplay. Other than 2-3 profiled guards, where the buckler is held straight out and the sword reserved (with the body profiled as in Olympic fencing), all of the guards of Khevsur swordplay are based on the joined buckler-sword position. The blade can shift around the buckler hand, which remains thumb side upright, but the sword hand always hides behind the buckler, and the buckler stays on the center line for protection.

Elashvili, the Georgian fencing master, wrote in his book Parikaoba, that from this position, you make a cut by projecting your hands forward together and chopping downward with the wrist and elbow. In fact, he states that the hands staying close together is perhaps THE defining characteristic of Khevsur swordplay. In the friendlier forms, where the fighters do not want to seriously injure or kill each other, this is certainly true, but this becomes less so once fighting more seriously. In war, cuts were made to and from the profiled guards as well, which deliver a far stronger impact than those made with joined or nearly joined hands. The oldest ethnographic film we have seems to show two primary modes of cutting: one where the hands remain joined behind the buckler and both move forward together, and one where the sword hand essentially darts forward to strike and immediately retreats behind the buckler. As this form of swordplay was passed down in villages and among family members, this variation in technique is possibly indicative of specific sub-schools among the Khevsur with distinctions that are now lost to us.

Just as we strike by projecting joined or adjacent hands forward, the Khevsur solution to blocking strikes is in essence to punch forward and towards the strike, catching it on the rim of the buckler. The sword is aligned in the plane of the incoming strike, and used to prevent the blade from sliding down the buckler edge and reaching the fighter. You twist your body to align your structure behind the block, with your arms reaching upward or downward as needed, being careful not to block your line of sight with the buckler or your hands. From this ‘catch’ position, an immediate riposte can be delivered in the same plane as the incoming strike, without exposing you to the incoming blade. On the whole, the buckler is used very offensively in Khevsur swordplay, so much so that the Khevsur have a saying: “The sword goes to work. The buckler blazes the path!” The Khevsur answer to most inbound strikes, though perhaps excluding some thrusts, can be summed up as: “Punch it with your buckler!”

Perhaps the most crucial element, the hardest to master in buckler use, is the constant tiny motions that the buckler makes in support of the sword hand. If someone is not well versed in buckler use, it would be easy to see the buckler as a largely static object, as if it is a simple impediment to the opponent’s blade. In reality, it acts in a very aggressive manner: pushing, striking, and creating openings for the sword to enter and do damage while protecting the sword hand as well as the rest of the wielder.

In addition to blocking with the buckler, it is used as an offensive weapon in its own right. Common offensive buckler techniques include the following actions, each performed after transferring a stopped sword from your buckler rim to your sword in order to hold it away from you:

- Punching forward to the opponent’s face with your buckler.

- Chopping the edge of the buckler down on your opponent’s sword arm at the wrist, to numb his hand and cause him to drop his sword

- Using a kindjal, held point down in your buckler hand, to stab your opponent in the arm or hook his wrist and pull it aside. (ideally cutting him as you do so).

Another characteristic action in Khevsur swordplay is a rather extreme form of level-shifting, wherein a fighter will drop into a very low squat or even to one knee and continue fighting. This may be done for multiple reasons, but at its simplest, it is to reduce your vulnerable target area and get under an opponent’s guard. One way that has proven highly effective in my own practice is to strike two or three hard downward blows at the junction of your opponent’s sword and buckler, as if you wanted to split them apart and strike the hands (maybe you get lucky and you do!) This tends to draw an opponent’s block higher, to meet and brace against the incoming force. On the last strike, instead of striking hard, sink to your haunches raising your buckler up overhead to protect your high line, and drawing your sword hilt down to the ground dragging it across the face of their buckler and letting the point pop forward as it falls beneath their defense. You can immediately thrust upward to the arms, body or face.

Regardless of how you drop to the squatting position, once there, the fight carries on as normal. Both fighters may advance, circle, or on rare occasions, retreat while remaining in a crouch. Other than the point downward guards becoming a bit shallower to accommodate the ground, the entire system functions as it does when standing. Unlike the Khevsur, we urban and suburban humans rarely spend our entire lives walking up-and-down mountain sides to develop our legs, so modern practitioners seem to have a hard time handling these deep squats and crouches while maintaining the ability to move. [2]

It is useful to notice that the previously described level shift is the first time that the thrust has been mentioned here. The downside to Elashvili’s book Parikaoba, is that parikaoba, as mentioned before, is the friendliest of the three forms of Khevsur swordplay. For safety reasons, and because it’s more about showing off than serious combat, his book ignores the thrust. In contrast, modern practitioners are trying to preserve what remains of lashkroba (the most life-and-death focused of the three levels of intensity) and reconstruct as much as possible of what has been lost there. For that, the primary sources used are interviews and research trips made into the mountains of Khevsureti, to seek out the last few Khevsur elders who practiced the art seriously in their youth. We have learned from them that the thrust was used regularly in serious combat, and that it came in several specific forms. Most notable were a thrust from under the buckler, as seen before, but another with the hand high, and point low, thrusting down behind an opponent’s buckler at their arms or neck.

The buckler alone does not suffice in defending against a thrust. Far more effective is the technique of parrying with a sweeping action of the blade to clear the thrust away from the body and following up by either striking directly with the buckler, or transferring his blade from your sword to your buckler, thus freeing your sword for the riposte.

The reality is that much of what we know about Khevsur swordplay is either reconstructed from the few written sources, or gleaned from research trips made up to the Khevsur highlands by martial scholars such as Niko Abazadze and the late Kakha Zarnadze, who sought to preserve the remaining knowledge and skills as best they could. Bits from one such research trip can be seen on YouTube as the trailer for a film project, In the Land of the Lost Crusaders, that sadly never came to completion. This was a project that followed Niko Abazadze and his student Vakhtang Kiziria on a research trip up to Khevsureti to learn from some of the last swordsmen to have practiced this seriously in their youth. Work continues still among various groups in Georgia and the USA to identify and fill in the gaps in our knowledge of the Khevsur fighting style, as well as to document other fragments of remaining arts from other regions of Georgia. The western Georgian region of Guria, as well as contributing the famed “cossack riders” to Buffalo Bill’s Wild West Show, also preserved some unique forms of sabre, and a two sword form of fighting, at least in part. Other regions preserved methods for fighting with the khanjali, or with the gajia fighting ring. But nowhere else in Georgia were the armed fighting styles preserved as completely as the sword-and-buckler fighting of Khevsureti.

[1] Photo Credit Shatvili Village – by Paata Vardanashvili from Tbilisi, Georgia, CC BY 2.0, Wikimedia Commons

[2] NOTE: Should you seek out video of this online, much of what is publicly posted on video-sharing sites by groups in Georgia is very much the flashy Hollywood-style side of things. If you see people leaping and spinning in a video, it is almost certainly the group showing off and trying to draw in practitioners to their reconstructed forms. These reconstructions are perhaps more an imagining of history as they wish it were rather than true historical reconstruction.

No part of this material may be reproduced in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, without permission in writing from the author. However, you are welcome to share a link to this article on such social media as Facebook, LinkedIn or Twitter.

Gary Harper

I’ve come across this before but it’s fascinating stuff. Wasn’t there a book called twenty league boots about this or a similar “crusader” fighting style. Thank you for the article Mike and thank you for posting Ellis.

Ellis Amdur

The book you are thinking of is Richard Halliburton’s Seven League Boots, and there is a chapter that does concern the Khevsurs. Not very accurately: dramatic, ethnocentric, incorrect in many particulars . . . https://tinyurl.com/14a3qtm8

Gary

Ah well, only 13 leagues out. That’s less than 45 miles!

Vakhtang

Dear Ellis,

Respectfully, I think such assessment of Halliburton’s work does him a bit of injustice. His kin eye and thorough attention to local lore and details of local customs( if course within limits of a brief contact) produced works that superseded in quality many of professional Ethnographic surveys of his contemporaries. He was perhaps one the most progressive Americans of his time( for instance check his chapter on Negroes of Abkhazia ( Western Georgia). His ethnocentrism is benign in it’s essence. There is not a single grain of a colonial messianism potentially set to ” educate the backwardness of the rest of the world ” Summarizing his chapter on Khevsurety I would say he is very accurate. Otherwise his ethnocentrism is very healthy mirror that places locality in a larger discourse and actually insights interest and further study. As of Crusaders myth he simply repeated what he was told by some local jokesters, he was not the first. In order to see the difference in journalistic quality, I suggest to check a chapter on Khevsurety in 12 secrets of the Caucasus by Essad Bey ( real name D. Nassenbaum) published only a decade before Halliburton’s Seven League Boots.

P.S. Halliburton’s integrity, boldness if not bravery, persistence and journalistic drive is evident from his interview with a dying executioner of Tsar’s family, which he successfully attempted already with the Soviet NKVD hot on his heels.

Ellis Amdur

Vakhtang – Thank you very much for the added information. You move me to read him again – he so excited my imagination as a young man.

James B. Evans

Thank you for this glimpse into the past. The part about hitting with a rock reminded me of a Takeda quote, ” crush him down to your feet, don’t throw him away”.

Ellis Amdur

Don’t think it’s quite the same. Takeda is talking about how to best effect victory in unarmed hand-to-hand combat. The Khevsurs are asserting that unarmed hand-to-hand combat is an absurdity; there’s always something that can be used as a weapon.

Vakhtang

Yes, it is an interesting phenomenon. Elsewhere in Caucasus we see rich variety of unarmed wrestling and boxing, however among Khevsurians any wrestling moves are just inherent elements of armed combat. Sociology of archaic militarised communities is welcome to dig into this 🙂

Mike Cherba

If anyone ins interested, a good friend stopped by the other day to test out some new swords I had made for use with the Georgian style. Here are some clips of our friendly exchanges while we tested out the new sparring blades.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=JYc9GZ0AAC0