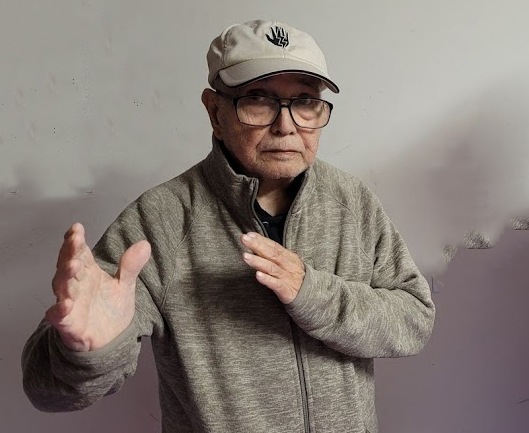

Some time ago, Ellis Amdur asked me if I’d be interested in contributing a guest post for the site. Knowing of my friendship with the renowned grappling expert, “Judo” Gene LeBell, and aware of Gene’s past relationship with the famed budoka, Donn Draeger, Ellis thought I might be able to offer some of Gene’s recollections to provide a different-than-usual take on Draeger, and the martial arts of a bygone era.

While Gene’s memory for details has faded a bit with time, I’ve had a number of extensive conversations with him in the past for various magazine articles, not to mention an aborted collaboration on his first attempt at an autobiography years ago. So I’m probably as qualified as anyone to share his impressions on these matters.

As far as Draeger goes, Gene always spoke very highly of him. “A great judo man” and “the best with weapons” was how he described Draeger to me on one occasion, opinions which probably won’t surprise anyone familiar with Draeger’s career in the martial arts. A generation older than Gene, Draeger came out of that pre-war school of judo which the early Japanese instructors in the West employed. My sense of that type of judo, both from talking to Gene and my own research, is that it was a somewhat more combative style, one laced with a bit more groundwork than would come to be the norm in the postwar years. That’s the style Gene appreciated, and I think he respected that “hardcore” approach in Draeger’s style.